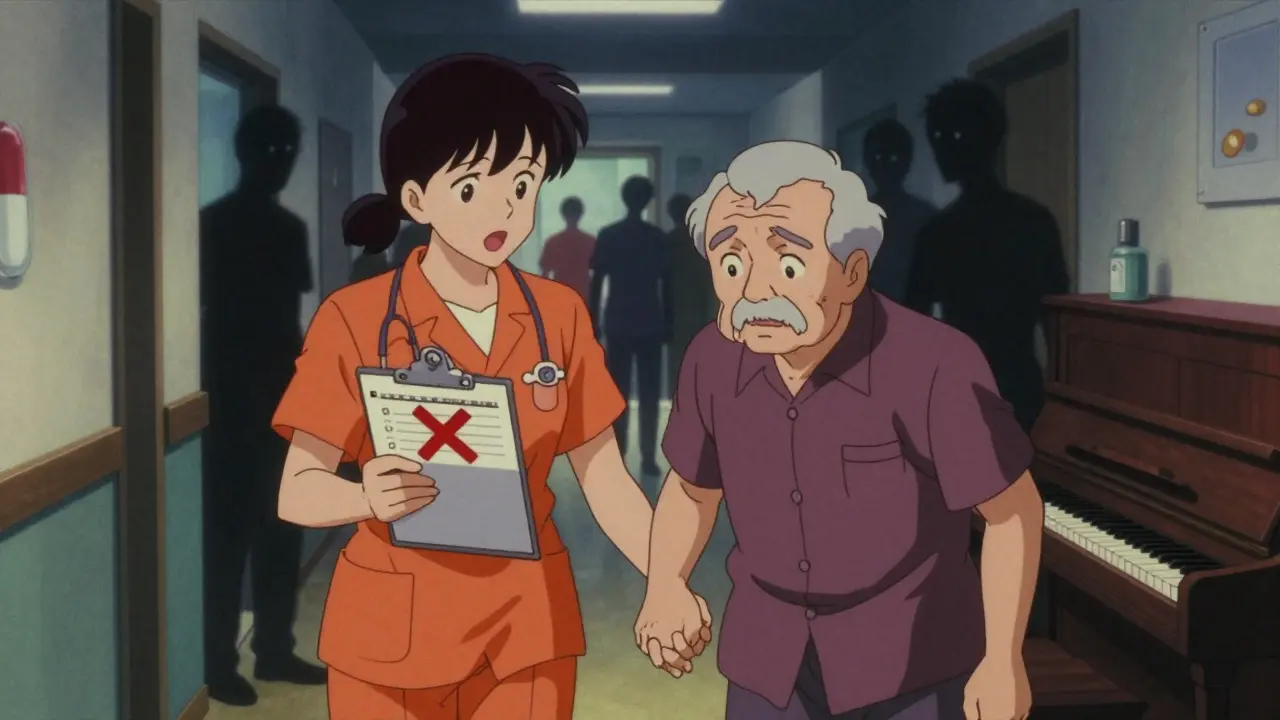

Every year, thousands of seniors with dementia are prescribed antipsychotic drugs to calm agitation, aggression, or hallucinations. But what if those drugs are putting them at greater risk of stroke - or even death? The answer isn’t just a yes. It’s a loud, well-documented warning that’s been out for nearly 20 years - and yet, many are still being given.

Why Antipsychotics Are Used (and Why They Shouldn’t Be)

When someone with dementia becomes agitated, restless, or even violent, families and caregivers often feel desperate. They want relief. Antipsychotics - drugs like Risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic commonly prescribed for behavioral symptoms in dementia, Olanzapine, a second-generation antipsychotic with metabolic side effects, or Haloperidol, a first-generation antipsychotic with high neurological side effect risk - seem like a quick fix. But they’re not a cure. They’re a chemical restraint.

The FDA issued a black box warning in 2005 - its strongest alert - after analyzing 17 studies involving over 4,000 elderly dementia patients. The results? Those taking antipsychotics had a 1.6 to 1.7 times higher risk of death than those on placebo. Stroke was one of the leading causes. The warning applied to both older (typical) and newer (atypical) antipsychotics. Since then, every major clinical guideline, including the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria, a widely referenced list of potentially inappropriate medications for older adults, has said: Don’t use these for dementia behavior unless there’s no other option.

The Real Risk: Stroke Isn’t Just a Possibility - It’s a Probability

Many assume that stroke risk only shows up after months of use. That’s wrong. A major 2012 study from the American Heart Association, a leading authority on cardiovascular health looked at over 100,000 older adults on Medicare and found something shocking: even a few days on an antipsychotic raised stroke risk by 80%. That’s not a slow buildup. It’s an immediate spike.

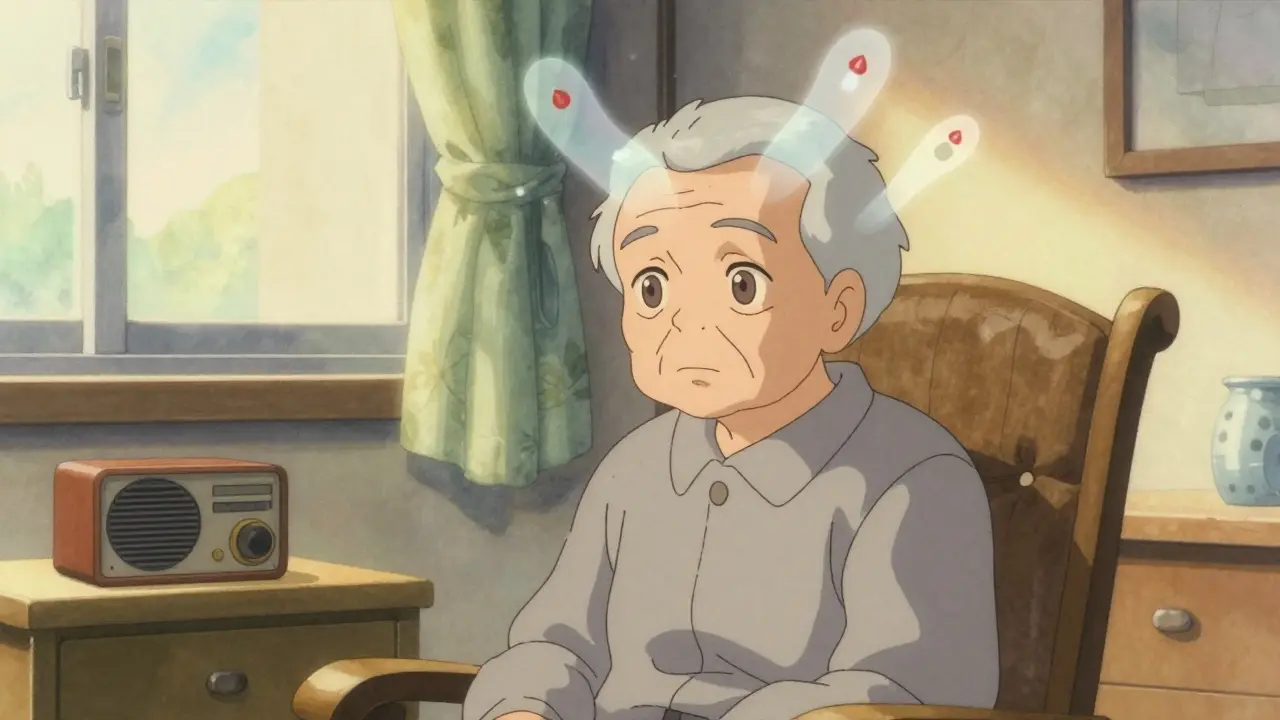

How does this happen? Antipsychotics don’t just affect dopamine. They mess with blood pressure regulation, cause sudden drops in blood pressure when standing (orthostatic hypotension), and trigger metabolic changes that raise blood sugar and cholesterol. All of these are known stroke triggers. A 2015 study in the American Journal of Epidemiology, a peer-reviewed journal focused on population health patterns showed that these drugs also thicken blood vessels and reduce blood flow to the brain - even in people who never had a stroke before.

And it’s not just one class of drugs. Both first-generation antipsychotics (like Haloperidol) and second-generation ones (like Risperidone) carry this risk. Some studies suggest the older drugs may be slightly worse, but the difference is small. The bottom line? Any antipsychotic used in dementia raises stroke risk.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just age. The risk climbs sharply in people who already have:

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- A history of heart disease or prior stroke

- Dehydration or poor nutrition

- Advanced dementia (especially in nursing homes)

One study of 32,710 Canadians with dementia found that stroke rates were nearly identical between those on older versus newer antipsychotics. Another study of nearly 5,000 nursing home residents showed the same pattern. The drugs might look different on a label, but their effect on the brain’s blood supply? Very similar.

Even more troubling? The more confused or aggressive the person becomes, the more likely they are to be prescribed these drugs. But that confusion might not be the cause - it might be the result of early brain damage from small, undetected strokes. In other words, the symptom doctors are trying to treat might already be a warning sign of something worse.

Why Are These Drugs Still Prescribed?

If the risks are this clear, why are antipsychotics still used in 1 in 4 nursing home residents with dementia? The answer is messy.

- Staff shortages: Managing aggression without drugs takes time, training, and staff - things many facilities lack.

- Family pressure: Families often ask, "Can’t you just give him something to calm down?"

- Lack of alternatives: Most providers aren’t trained in non-drug approaches.

- Legal and insurance loopholes: In some cases, antipsychotics are used as "behavioral management" rather than "treatment," sidestepping stricter rules.

The American Geriatrics Society, a professional organization focused on elderly health care says non-drug strategies should always come first. But in practice, they’re often skipped.

What Should Be Done Instead?

There are proven, safer ways to manage behavioral symptoms in dementia - and they don’t come in a pill.

- Environmental changes: Reduce noise, improve lighting, eliminate clutter. A calm space reduces agitation.

- Structured routines: People with dementia do better with predictability. Consistent meal, bathing, and bedtime times help.

- Person-centered care: What’s the person trying to communicate? Pain? Boredom? Fear? Often, the behavior is a cry for help.

- Music therapy: Studies show familiar music can reduce aggression more effectively than drugs in some cases.

- Physical activity: Even short walks or seated exercises lower agitation and improve sleep.

- Staff training: Caregivers who understand dementia behavior are less likely to reach for medication.

One nursing home in Oregon cut antipsychotic use by 70% in two years by training staff to recognize triggers and respond with redirection, not drugs. No lawsuits. No deaths. Just better care.

The Bottom Line

If your loved one with dementia is on an antipsychotic, ask these questions:

- Why was this prescribed? What symptom is it targeting?

- Has every non-drug option been tried?

- How long have they been on it? Is this long-term or short-term?

- What are the signs of stroke I should watch for? (Sudden confusion, slurred speech, weakness on one side, loss of balance)

The FDA warning didn’t disappear. The science hasn’t changed. The risks are real - and they’re immediate. Antipsychotics aren’t just risky. In dementia, they’re often the wrong choice. There are better ways. They just take more time, more patience, and more care.

Are atypical antipsychotics safer than typical ones for seniors with dementia?

No, not really. While atypical antipsychotics like Risperidone or Quetiapine were once thought to be safer, research shows both types carry nearly equal stroke risk in elderly dementia patients. The difference is small, and both can cause serious side effects like metabolic changes, low blood pressure, and increased death risk. The FDA warning applies to all antipsychotics, regardless of generation.

Can antipsychotics cause stroke after just a few days of use?

Yes. A large 2012 study from the American Heart Association found that stroke risk rises sharply within the first week of starting an antipsychotic. Even brief exposure - as little as 3 to 5 days - can increase stroke risk by 80%. This contradicts the old belief that only long-term use was dangerous.

Why do doctors still prescribe antipsychotics if they’re so risky?

Many doctors prescribe them because they’re under pressure - from families, from understaffed facilities, or from a lack of training in non-drug alternatives. Some believe the drugs are necessary for safety. But guidelines from the American Geriatrics Society and the FDA clearly state that non-drug approaches should be tried first. Prescribing continues due to systemic gaps in dementia care, not because the drugs are safe.

What are the signs of stroke I should watch for in a senior on antipsychotics?

Watch for sudden changes: slurred speech, weakness on one side of the body, drooping face, confusion, trouble walking, loss of balance, or a severe headache with no known cause. These can happen quickly - sometimes within hours. If you notice any of these, call 911 immediately. Don’t wait. Antipsychotics can make stroke more likely, and early treatment saves lives.

Are there any legal or ethical concerns with using antipsychotics for dementia behavior?

Yes. Using antipsychotics to control behavior without consent - especially in nursing homes - can be considered chemical restraint, which is legally and ethically questionable. Many states now require documentation proving non-drug options were tried before prescribing. The FDA and American Geriatrics Society both state these drugs should only be used when behavior poses an immediate threat to safety - and even then, only briefly and with close monitoring.

What should I do if my loved one is already on an antipsychotic?

Don’t stop the drug suddenly - that can cause dangerous withdrawal. Talk to the prescribing doctor about tapering off, and ask for a plan to replace it with non-drug strategies. Bring up the FDA warning and the American Geriatrics Society guidelines. Request a medication review. Many people improve once the drug is slowly reduced, especially with better environmental support and caregiver training.

What’s Next?

The science is clear. The warnings are loud. But change won’t come from another study. It will come when families ask, "Is this really necessary?" when caregivers say, "We can handle this without drugs," and when doctors choose patience over pills.

If you’re caring for someone with dementia, you’re not alone. But you don’t have to accept the status quo. Ask questions. Push for alternatives. Demand better. Because sometimes, the most powerful medicine isn’t a pill - it’s your voice.

Brad Ralph

February 11, 2026 AT 01:16Stacie Willhite

February 12, 2026 AT 12:23christian jon

February 13, 2026 AT 19:15Vamsi Krishna

February 15, 2026 AT 15:21Jason Pascoe

February 17, 2026 AT 00:21Sonja Stoces

February 17, 2026 AT 22:17Annie Joyce

February 18, 2026 AT 06:34Rob Turner

February 18, 2026 AT 18:04Luke Trouten

February 20, 2026 AT 06:16Gabriella Adams

February 20, 2026 AT 19:25Kristin Jarecki

February 22, 2026 AT 04:37Jonathan Noe

February 22, 2026 AT 06:37Rachidi Toupé GAGNON

February 22, 2026 AT 11:27Jim Johnson

February 23, 2026 AT 15:49