Steroid & PPI Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps determine if you need a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) while taking corticosteroids. Based on evidence from the article, most patients taking steroids alone do NOT need PPIs.

Your Risk Factors

Enter your information to see if you need a PPI

For years, doctors have automatically prescribed proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to patients on corticosteroids-just in case. But what if that routine is doing more harm than good? The truth is, corticosteroids alone rarely cause gastric ulcers. Yet many patients still get PPIs prescribed out of habit, not evidence. This isn’t just unnecessary-it increases the risk of infections, nutrient deficiencies, and kidney problems. So how do you actually prevent and monitor for gastric ulcers when using steroids? Let’s cut through the noise.

Do Corticosteroids Alone Cause Ulcers?

The short answer: not really. Large studies, including a 2013 review of over 1 million patients, found no significant link between corticosteroid use alone and peptic ulcer disease. In fact, the rate of ulcers in people taking steroids by themselves was between 0.4% and 1.8%. That’s lower than many common medications. So why do we think they cause ulcers? Because symptoms like stomach burning or nausea are common with steroids, and those symptoms get mistaken for ulcers. But pain doesn’t always mean damage.

The bigger issue? Corticosteroids hide symptoms. They reduce inflammation, so if an ulcer is forming, you might not feel it until it bleeds or perforates. That’s dangerous-but not because steroids cause ulcers. It’s because they mask the warning signs.

The Real Danger: When Steroids Meet NSAIDs

The real risk comes when corticosteroids are mixed with NSAIDs-drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, or aspirin. Studies show that when taken together, the chance of a serious GI bleed jumps by more than four times. One study of Medicaid patients found a relative risk of 4.4 (95% CI, 2-9.7). That’s not a small number. It’s a red flag.

Think about it this way: if you’re on prednisone for a flare-up of rheumatoid arthritis and you’re also taking Advil for joint pain, you’re stacking two drugs that damage the stomach lining. Neither one alone is likely to cause trouble. Together? That’s when things go wrong.

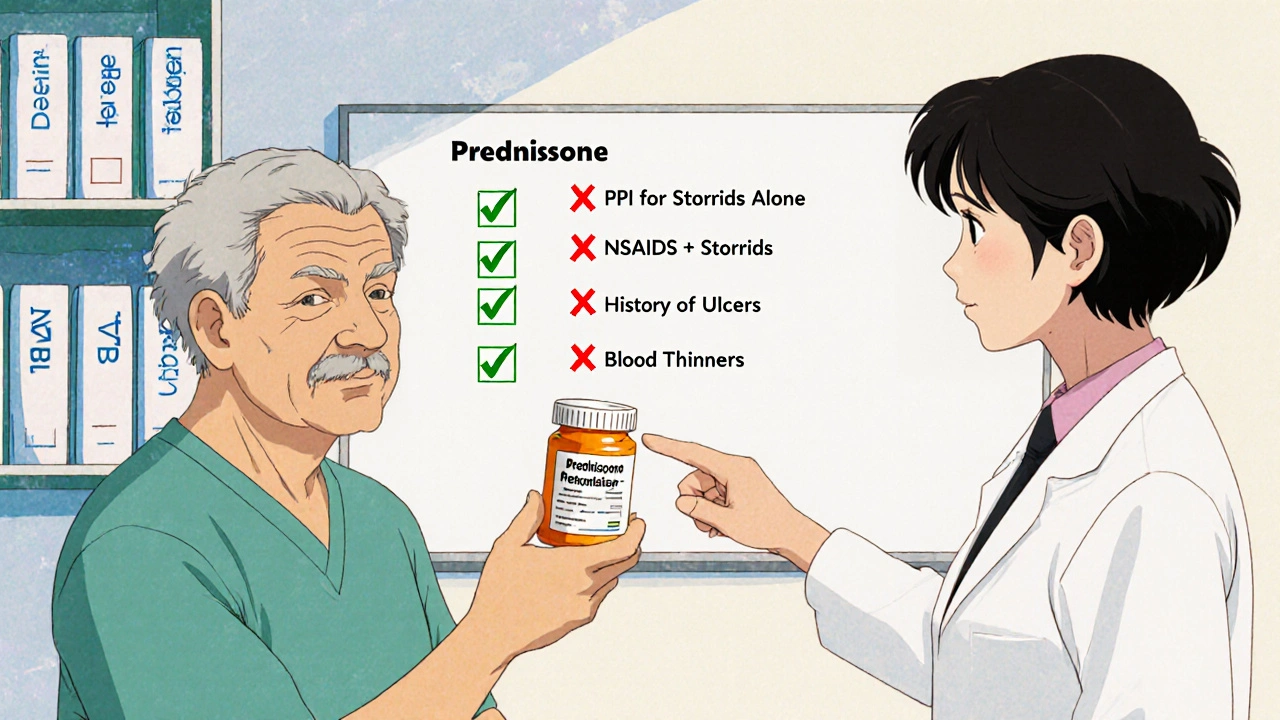

Who Actually Needs Prophylaxis?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole or pantoprazole are not needed for everyone on steroids. A 2023 article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, part of the Things We Do for No Reason™ initiative, called out routine PPI use in steroid-only patients as an example of overmedicalization. At Johns Hopkins, a quality project stopped giving PPIs to patients on steroids without NSAIDs-and saw no rise in GI complications over 12 months. PPI use dropped by 42.7%.

So who should get a PPI? Only these people:

- Those taking both corticosteroids and NSAIDs

- Patients with a history of peptic ulcer or GI bleeding

- People on anticoagulants like warfarin or apixaban

- Those with confirmed Helicobacter pylori infection

- Patients hospitalized and on high-dose steroids (over 20mg prednisone daily)

For everyone else, PPIs add risk without benefit. Long-term PPI use is linked to lower magnesium levels, increased risk of pneumonia, and even kidney injury. Don’t treat a ghost.

Monitoring: What to Watch For

Monitoring doesn’t mean regular endoscopies or blood tests. It means paying attention to symptoms-and knowing which ones matter.

At every follow-up visit, ask:

- Have you had black, tarry stools? (That’s melena-sign of bleeding)

- Have you vomited blood or material that looks like coffee grounds?

- Are you feeling unusually tired, dizzy, or short of breath? (Signs of anemia from slow bleeding)

- Is your stomach pain getting worse, or not improving?

If any of these are yes, get an endoscopy. No need to wait. But if you’re just feeling a little bloated or have mild heartburn? That’s probably just the steroid. Don’t jump to an ulcer diagnosis.

Also, check blood sugar. Corticosteroids spike glucose levels, especially after meals. Fasting glucose might look fine, but post-meal spikes are common and often missed. A simple finger stick after lunch can catch steroid-induced insulin resistance early.

What About Hospitalized Patients?

This is where things change. A 2014 review in BMJ Open found hospitalized patients on corticosteroids had a 43% higher risk of GI bleeding (OR 1.43). Why? Because they’re sicker. They’re often on multiple drugs, have reduced blood flow, and may be on ventilators or feeding tubes-all of which stress the GI tract.

For patients in the ICU or on high-dose steroids (like 60mg prednisone or more), prophylaxis with a PPI is still reasonable. But even here, it should be time-limited. Once they’re stable and off steroids, stop the PPI. Don’t let it become a lifelong habit.

The Bigger Picture: Overprescribing PPIs

More than 78% of hospitalists still prescribe PPIs to steroid-only patients, even though 63% admit the evidence is weak. Why? Fear. One doctor on Reddit said they stopped routine PPIs after reading the Things We Do for No Reason™ article-and hadn’t seen a single GI bleed in 18 months. Another said they had a patient bleed out on 60mg of prednisone alone and swore they’d never skip PPIs again.

But one case doesn’t change the data. The overall risk for ambulatory patients is 0.12 events per 100 person-years. That’s less than 1 in 1,000 people per year. If you’re prescribing PPIs to 100 people on steroids, you’re giving 100 people a drug with known long-term risks to prevent one possible event.

At the University of Wisconsin, they created a Steroid-Only PPI Stewardship Protocol in early 2023. It cut inappropriate PPI prescriptions by 35%. No increase in complications. That’s the future.

What’s Next? Research Is Catching Up

The American Gastroenterological Association is now reviewing corticosteroid-related GI risks for their 2025 guidelines. A clinical trial on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05214345) is directly comparing GI outcomes in steroid users with and without PPIs. Results are expected by late 2024.

Until then, stick to the evidence. Don’t give PPIs because it’s what’s always been done. Give them because the data says to.

Bottom Line: Smart Prevention, Not Blanket Coverage

Corticosteroids don’t cause ulcers on their own. They make ulcers harder to detect. The real threat is combining them with NSAIDs or other risk factors. Prevention isn’t about popping a pill every day-it’s about knowing who’s at real risk and who isn’t.

Here’s your simple checklist:

- Are you on NSAIDs? → Yes? Take a PPI.

- History of ulcers or GI bleed? → Yes? Take a PPI.

- On blood thinners? → Yes? Take a PPI.

- Admitted to the hospital on high-dose steroids? → Yes? Take a PPI for now.

- Just on steroids at home, no other risks? → No PPI needed.

Monitor for alarm symptoms. Don’t assume every stomach ache is an ulcer. And never keep a PPI on auto-pilot. Stop it when the steroid does.

Do corticosteroids cause stomach ulcers on their own?

No, corticosteroids alone do not significantly increase the risk of gastric ulcers. Large studies show ulcer rates in steroid-only users are between 0.4% and 1.8%, similar to the general population. Symptoms like stomach burning are common but rarely indicate actual ulcers. The real danger comes when steroids are combined with NSAIDs or other risk factors.

Should everyone on prednisone take a PPI?

No. Routine PPI use for corticosteroid monotherapy is not supported by evidence. Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Wisconsin show no increase in GI complications when PPIs are stopped in patients taking steroids alone. PPIs should only be used if you’re also taking NSAIDs, have a history of ulcers, are on blood thinners, or are hospitalized on high-dose steroids.

What are the risks of taking PPIs long-term?

Long-term PPI use can lead to low magnesium levels, increased risk of pneumonia, Clostridioides difficile infection, and kidney damage. It may also interfere with absorption of vitamin B12 and calcium. For people on steroids without other risk factors, the risks of PPIs outweigh the benefits.

How do I know if I have a steroid-related ulcer?

Look for alarm symptoms: black or tarry stools, vomiting blood, unexplained fatigue or dizziness (signs of anemia), or persistent, worsening stomach pain. Mild bloating or heartburn is usually not an ulcer-it’s a side effect of the steroid. If you have alarm symptoms, get an endoscopy. Don’t wait.

Is monitoring blood sugar important when taking steroids?

Yes. Corticosteroids cause blood sugar spikes, especially after meals. Fasting glucose may appear normal, but postprandial levels can rise sharply. A simple finger stick after lunch can catch early signs of steroid-induced insulin resistance. Monitoring glucose helps prevent long-term metabolic complications.

What should I do if I’m on both steroids and ibuprofen?

Stop taking ibuprofen if possible. Use acetaminophen for pain instead. If you must take an NSAID, combine it with a PPI. The risk of GI bleeding jumps more than four times when steroids and NSAIDs are used together. Don’t rely on your body to warn you-this combo is dangerous.

What to Do Next

If you’re on corticosteroids and not on NSAIDs, ask your doctor: "Do I really need a PPI?" Show them the evidence. If you’re in the hospital and on high-dose steroids, ask if a PPI is necessary-and for how long. If you’ve been on a PPI for months or years just because you’re on steroids, it’s time to talk about stopping it.

Don’t let outdated habits drive your care. The data is clear: most people on steroids don’t need PPIs. The goal isn’t to prevent every possible problem-it’s to prevent real problems without creating new ones.

Neoma Geoghegan

November 23, 2025 AT 17:05Stop overtreating.

Bartholemy Tuite

November 24, 2025 AT 16:04no one asked if i was on ibuprofen or had a history of ulcers

just ‘here take this forever’

then i read this thread and realized i was being medicalized like a lab rat

stopped the ppi after 3 months and nothing happened

my stomach didn’t explode

my kidneys are fine

my life is better

we need to stop treating symptoms like diagnoses

Sam Jepsen

November 26, 2025 AT 04:13Yvonne Franklin

November 26, 2025 AT 08:40Stop ordering endoscopies for every stomach ache.

Patrick Marsh

November 27, 2025 AT 19:12Danny Nicholls

November 29, 2025 AT 18:25My aunt was on prednisone for lupus and got a PPI for 3 years. Then she got C. diff. Twice. Then her B12 dropped to 180. She’s fine now but… why? Why give her the pill in the first place?

Thank you for this. Sharing with my whole family.

Robin Johnson

November 30, 2025 AT 08:38Latonya Elarms-Radford

December 1, 2025 AT 10:38Mark Williams

December 2, 2025 AT 01:38Daniel Jean-Baptiste

December 2, 2025 AT 19:36Ravi Kumar Gupta

December 4, 2025 AT 04:31