When you get a shot in the hospital, you expect it to be safe. You don’t think about the air around it, the gloves the technician wore, or how many times the vial was cleaned before it reached your arm. But behind every injectable drug-whether it’s insulin, chemotherapy, or a COVID vaccine-is a complex, tightly controlled process designed to keep out every single microbe. This isn’t just good practice. It’s life or death.

Why Sterility Isn’t Optional for Injectables

Oral pills go through your stomach, where acid kills most bacteria. Injectables don’t have that luxury. They go straight into your bloodstream. One live bacterium can trigger sepsis. One molecule of endotoxin can cause fever, shock, or death. That’s why sterile manufacturing exists: to guarantee that every dose is free of contaminants. The stakes became terrifyingly clear in 2012, when contaminated steroid injections from the New England Compounding Center led to 751 infections and 64 deaths. The CDC traced it back to poor sterile technique. That outbreak didn’t just hurt patients-it changed regulations forever. Today, the global standard demands a contamination probability of less than one in a million (SAL 10-6). That means, statistically, out of a million vials, no more than one should be contaminated. It’s not a guess. It’s a validated requirement backed by the WHO, FDA, and EU.Two Paths to Sterility: Terminal vs. Aseptic

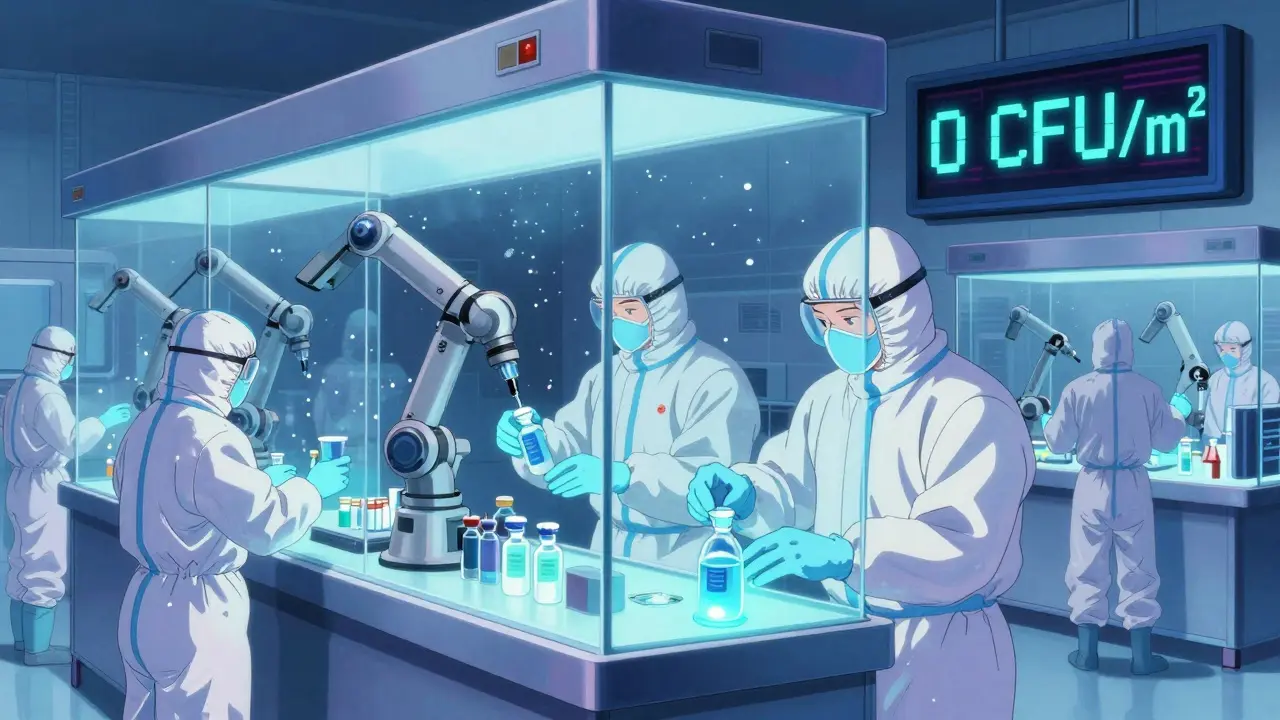

There are two main ways to make sterile injectables, and the choice depends on what’s inside the vial. Terminal sterilization is the gold standard when possible. The filled vial-sealed with its cap and stopper-is put into an autoclave and blasted with steam at 121°C for 15 to 20 minutes. This kills everything. It’s simple, reliable, and costs about $50,000 per batch. But here’s the catch: it only works for about 30-40% of injectables. Heat-sensitive drugs like monoclonal antibodies, proteins, and some vaccines would break down. They’d lose their effectiveness. That’s where aseptic fill-finish comes in. Instead of sterilizing the final product, you sterilize everything before you fill it. The drug solution, the vials, the stoppers, the machines, even the air in the room-all must be sterile. This happens in an ISO 5 cleanroom, also known as a Class 100 room. That means fewer than 3,520 particles larger than 0.5 microns per cubic meter of air. For comparison, a typical city street has over 10 million. Aseptic processing is more expensive-$120,000 to $150,000 per batch-and far more complex. But it’s the only way to make modern biologics. Over 70% of new drug candidates today are too fragile for heat. That’s why aseptic processing now dominates the market.What Makes a Cleanroom Truly Clean

You can’t just build a room and call it sterile. It’s a system. Every detail matters. - Airflow: In ISO 5 zones, air moves in one direction-like a silent waterfall-over the filling line. Speed: 0.3 to 0.5 meters per second. Too slow, and particles settle. Too fast, and it creates turbulence. - Pressure: Rooms are kept under positive pressure. The filling room is at 10-15 Pascals higher than the gowning area, which is higher than the corridor. Air flows out, never in. Contaminants can’t sneak in. - Temperature and humidity: 20-24°C and 45-55% RH. Why? Too cold, and condensation forms. Too humid, and microbes thrive. - Water for Injection (WFI): This isn’t purified water. It’s ultra-pure. Endotoxin levels must be under 0.25 EU/mL. That’s stricter than drinking water standards by a factor of 1,000. - Depyrogenation: Glass vials and stoppers are baked at 250°C for 30 minutes. Why? Because endotoxins (toxic parts of dead bacteria) survive boiling. Only intense dry heat destroys them.

Technology That Keeps Things Safe

Two main systems handle aseptic filling: RABS and isolators. RABS (Restricted Access Barrier Systems) are like glass booths with gloves built in. Technicians reach in to load vials and change supplies. They’re cheaper and easier to use but still rely on human skill. Isolators are fully sealed, automated chambers. Everything enters through airlocks or UV-sterilized transfer ports. No human hands touch anything inside. Isolators reduce contamination risk by 100 to 1,000 times, according to Dr. James Akers. But they cost 40% more to install. The industry is shifting. In 2023, 65% of new sterile facilities chose closed, automated systems. Why? Because human error is the biggest cause of contamination. A senior manager at a top pharma company lost $450,000 in one batch because a glove in their RABS system had a tiny tear. That’s not rare.Testing for Safety: Media Fills and Monitoring

You can’t just assume it’s sterile. You have to prove it. Media fill simulations are the most critical test. Instead of real drug, you fill vials with growth medium-nutrient broth that feeds bacteria. You run the whole process as if you’re making real product. Then you incubate the vials for 14 days. If any grow microbes, the whole process fails. FDA says: if your failure rate is above 0.1%, your system isn’t under control. That’s one failed vial in a thousand. Most companies aim for zero. Real-time monitoring is now mandatory. Particle counters run continuously. Air samplers pull in air and trap microbes. In ISO 5 zones, the alert level is 1 CFU/m³. If you hit 5 CFU/m³, you shut down. No exceptions.

Costs, Challenges, and the Real-World Toll

Setting up a sterile manufacturing line isn’t cheap. A small facility with 5,000-10,000 liters annual capacity costs $50-100 million. That’s before you hire trained staff, buy equipment, or run validation tests. Personnel need 40-80 hours of training just to enter the cleanroom. They must pass media fill tests twice a year. Even then, 22% of FDA inspection failures are due to inadequate training. The financial cost of failure is brutal. A single sterility test failure averages $1.2 million. That’s not just lost product-it’s delayed shipments, regulatory penalties, and damaged trust. But there’s progress. One facility in Switzerland cut deviations by 45% and sped up batch releases by 30% after installing continuous monitoring systems. Another cut defects from 0.2% to 0.05% with automated visual inspection-though it cost $2.5 million.Regulations Are Getting Tighter

The EU’s revised Annex 1 (2022) changed everything. It requires: - Continuous environmental monitoring (no more spot checks) - Quality Risk Management (ICH Q9) built into every process - Validated cleaning procedures for every surface - Real-time data logging, not paper records The FDA followed with new guidance in 2023. They’re pushing for: - Advanced process controls - Digital twins to simulate operations before running them - AI tools to predict contamination risks By 2025, companies must spend $15-25 million to upgrade to meet these standards. Those who don’t will get flagged. In 2022, the FDA issued 1,872 inspection citations for sterile manufacturing issues-up from 1,245 in 2019.What’s Next?

The future of sterile manufacturing is automation, speed, and data. Robotic filling systems will grow 40% by 2027. Rapid microbiological tests will cut testing time from two weeks to 24 hours. Digital twins will let engineers test changes in a virtual environment before touching real equipment. And the demand? It’s skyrocketing. Sterile injectables made $225 billion in 2023. By 2028, that’s expected to hit $350 billion. Most of that growth comes from biologics-monoclonal antibodies, gene therapies, and personalized medicines. These drugs can’t be sterilized by heat. They demand aseptic processing. And they demand perfection. There’s no room for shortcuts. Every step-from the water you use, to the gloves your team wears, to the way you seal a vial-must be flawless. Because when a drug goes into a vein, there’s no second chance.What’s the difference between sterile and aseptic manufacturing?

Sterile manufacturing means the final product is free of microbes. Aseptic manufacturing is one method to achieve that-it’s the process of assembling sterile components without exposing them to contamination. Terminal sterilization (like autoclaving) is another method. Aseptic processing doesn’t sterilize the final product; it prevents contamination during production.

Why can’t all injectables be terminally sterilized?

Many injectables-especially biologics like monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and protein-based drugs-are too sensitive to heat or radiation. Steam at 121°C or gamma rays can destroy their structure, making them ineffective. These drugs require aseptic processing, where every component is sterilized separately and assembled in a sterile environment.

What is a media fill test, and why is it required?

A media fill test simulates the entire aseptic filling process using nutrient broth instead of the actual drug. After filling, the vials are incubated for 14 days to see if any microbes grow. If they do, the process failed. It’s the only way to prove that your cleanroom, procedures, and personnel can consistently produce sterile products. The FDA requires it for validation and requalification every six months.

How often do sterile manufacturing facilities fail inspections?

In 2022, 68% of FDA inspection deficiencies in sterile facilities were linked to aseptic technique failures. Common issues include poor gowning, inadequate environmental monitoring, and media fill failures. About 37% of inspections cited insufficient monitoring systems, and 28% found media fill failures. One in three facilities reports at least one sterility failure per year.

What’s the biggest risk in sterile manufacturing?

Human error. Even with the best equipment, people are the most common source of contamination-through improper gowning, movement in the cleanroom, glove tears, or lapses in procedure. That’s why isolators and automation are becoming standard. Reducing human contact with the product reduces risk dramatically.

shivani acharya

January 20, 2026 AT 22:22Neil Ellis

January 21, 2026 AT 17:26Hilary Miller

January 23, 2026 AT 12:15Daphne Mallari - Tolentino

January 24, 2026 AT 13:07Keith Helm

January 24, 2026 AT 13:29Brenda King

January 26, 2026 AT 01:14Malik Ronquillo

January 26, 2026 AT 20:54Liberty C

January 27, 2026 AT 17:01Sarvesh CK

January 29, 2026 AT 08:46Margaret Khaemba

January 30, 2026 AT 07:24