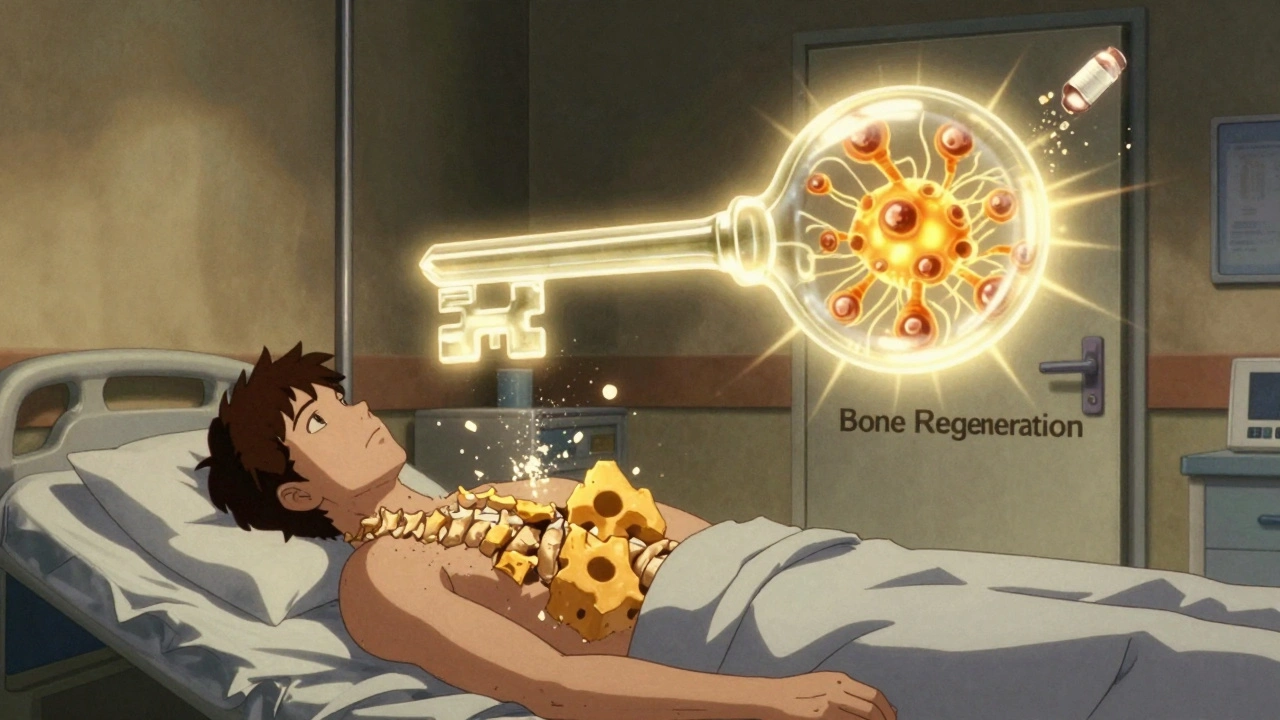

Over 80% of people diagnosed with multiple myeloma will develop serious bone damage. It’s not just weakness or aging - it’s a direct result of cancer cells rewriting the rules inside your bones. These cancerous plasma cells don’t just sit in the marrow. They activate bone-eating cells, shut down bone-building cells, and create holes that can turn into fractures with the slightest bump. This isn’t a side effect. It’s a core part of the disease. And for decades, treatment focused only on slowing the damage - not fixing it.

How Myeloma Turns Bones Into Swiss Cheese

Your bones aren’t static. They’re alive, constantly being broken down and rebuilt. Osteoclasts chew away old bone. Osteoblasts lay down new bone. In healthy people, these two work in perfect balance. In multiple myeloma, that balance shatters.Myeloma cells pump out signals that tell osteoclasts to go wild. One key signal is RANKL. Healthy bone has just enough RANKL to keep remodeling normal. Myeloma patients have three to five times more. At the same time, they suppress OPG, the natural brake on RANKL. The result? Bone erosion runs unchecked.

But it’s worse than that. Myeloma cells also block the Wnt pathway - the main system that tells osteoblasts to grow new bone. They do this by releasing DKK1 and sclerostin. Studies show patients with DKK1 levels above 48.3 pmol/L have more than three times the number of bone lesions. Sclerostin, a protein made by bone cells themselves, is also elevated - averaging 28.7 pmol/L in myeloma patients versus 19.3 in healthy people. These aren’t random spikes. They’re direct weapons.

The damage isn’t just deep. It’s local. Bone biopsies prove that osteoclasts cluster right next to myeloma cells. The cancer doesn’t just float around - it sets up camp and turns the bone around it into a war zone. And here’s the cruel twist: when bone breaks down, it releases growth factors that feed the myeloma cells. More cancer. More bone loss. A cycle that keeps spinning.

Standard Treatments: Slowing the Damage, Not Rebuilding

For years, the only tools we had were bisphosphonates and denosumab. Both aim to stop osteoclasts. Zoledronic acid and pamidronate are given intravenously every month. Denosumab is a shot under the skin, also monthly.They work - but only partially. Clinical trials show they reduce skeletal-related events (fractures, spinal cord compression, need for radiation) by 15% to 18%. That’s meaningful. But it’s not enough. Patients still break bones. Still need surgery. Still live with pain.

And there are costs. Zoledronic acid can hurt the kidneys. About 22% of patients need dose changes because their creatinine clearance drops below 60 mL/min. Denosumab doesn’t affect kidneys, but it can cause severe low calcium - 18.5% of patients need supplements just to stay safe. Then there’s MRONJ - medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. About 42% of patients on these drugs report dental problems serious enough to need surgery.

One patient on Reddit wrote: "I’ve been on zoledronic acid for three years. My teeth are falling apart. I can’t eat apples anymore. My doctor says it’s the drug. But he can’t fix it." That’s the reality. These drugs protect bones by freezing them - but they don’t heal them.

The New Wave: Drugs That Actually Build Bone

The real breakthrough isn’t in stopping bone loss. It’s in making bone grow again.Anti-sclerostin drugs like romosozumab and blosozumab are changing the game. Sclerostin blocks bone formation. Block sclerostin, and osteoblasts wake up. In the 2021 STRUCTURE trial, 49 myeloma patients on romosozumab saw a 53% increase in bone mineral density at the spine in just 12 months. That’s not slowing damage. That’s rebuilding.

Anti-DKK1 therapies like DKN-01 are also showing promise. In a 2020 trial with 32 patients, DKN-01 cut bone resorption markers by 38%. It doesn’t just stop the breakdown - it helps the body start building again.

Even gamma-secretase inhibitors, which block the Notch pathway (another signal myeloma uses to trigger bone destruction), have cut osteolytic lesions by 62% in animal models. Human trials are just beginning, but the early signs are strong.

These aren’t lab curiosities. They’re drugs designed to reverse what myeloma does to bone. Romosozumab patients reported a 35% improvement in pain scores. That’s not just numbers. That’s patients walking without pain, sleeping through the night, getting back to life.

Who Gets These New Drugs? And When?

Right now, these novel agents are mostly in clinical trials. Romosozumab is in a phase III trial called BONE-HEAL, enrolling 450 patients across the U.S. and Europe. It’s not FDA-approved for myeloma yet - but it is for osteoporosis.Doctors are starting to use them off-label in select cases. Patients with aggressive bone disease, high DKK1 or sclerostin levels, or those who’ve had multiple fractures despite bisphosphonates are candidates. The European Myeloma Network now says we should treat bone disease early - before fractures happen, not after.

But there’s a catch. These drugs aren’t cheap. Romosozumab costs about $2,500 per dose. Denosumab is $1,800. Generic zoledronic acid? $150. Insurance coverage varies wildly. In the U.S., denosumab is used in 78% of cases. In Europe, it’s only 42%. In Asia, bisphosphonates still dominate at 89%.

Cost isn’t the only barrier. Anti-sclerostin drugs require monthly calcium checks. Too much can cause heart rhythm problems. Too little, and you get seizures. Gamma-secretase inhibitors cause severe rashes in nearly 70% of patients. These aren’t simple pills. They need careful monitoring.

The Future: Healing Bones, Not Just Preventing Breaks

The goal isn’t just to prevent fractures. It’s to make bones whole again.Researchers are now testing bispecific antibodies that attack myeloma cells while also blocking bone-damaging signals. RNA therapies like Alnylam’s ALN-DKK1 are silencing the DKK1 gene in preclinical models - reducing the protein by 65%. That’s a direct hit on one of the main causes of bone loss.

And there’s a shift in thinking. We’re moving from treating bone disease as a complication to treating it as part of the cancer itself. Bone isn’t just a victim. It’s an active player. When you target both the cancer and the bone environment together, you break the cycle.

Dr. Brian Durie of the International Myeloma Foundation says we’ll be healing myeloma bone lesions by 2030. That’s not science fiction. It’s the direction we’re already moving.

What Patients Need to Know Now

If you have multiple myeloma, ask your doctor these questions:- Have I had a full bone scan - whole-body low-dose CT or PET-CT?

- What’s my DKK1 or sclerostin level? Is it high?

- Am I on the best bone drug for me - bisphosphonate, denosumab, or something else?

- Have I had a dental checkup in the last 30 days?

- Am I eligible for any clinical trials for new bone-building drugs?

Don’t wait for a fracture to act. Bone damage starts early. The earlier you target it, the better your chances of keeping your spine, hips, and ribs intact.

Resources like the Myeloma Beacon’s Bone Health Toolkit and the International Myeloma Foundation’s Bone Disease Guide have helped over 40,000 patients. Download them. Talk to your team. Ask for more than just pain control. Ask for healing.

The old way was to manage bone disease. The new way is to reverse it. And that’s the future - one bone at a time.

Can multiple myeloma bone disease be reversed?

Yes, in some cases. Traditional drugs like bisphosphonates and denosumab stop further damage but don’t rebuild bone. Newer agents like romosozumab (anti-sclerostin) and DKN-01 (anti-DKK1) have shown in clinical trials that they can actually increase bone mineral density and reduce bone lesions. In the STRUCTURE trial, patients saw a 53% increase in spine bone density after 12 months. While full healing isn’t guaranteed for everyone, these drugs are the first to show real bone regeneration in myeloma patients.

What’s the difference between denosumab and zoledronic acid?

Both stop bone breakdown, but they work differently. Zoledronic acid is an IV infusion given monthly. It stays in the bone for years and can harm kidney function - about 22% of patients need dose adjustments. Denosumab is a monthly shot under the skin. It doesn’t affect kidneys, but it can cause low calcium levels, which requires daily calcium and vitamin D supplements. Patients often prefer denosumab for convenience, but cost is higher - $1,800 per dose versus $150 for generic zoledronic acid.

Why do I need a dental checkup before starting bone drugs?

Medications like bisphosphonates and denosumab can cause a rare but serious condition called medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). This happens when the jawbone doesn’t heal after dental work - like extractions or implants. The risk is highest in the first 6 months of treatment. A dental exam before starting therapy lets your dentist fix any problems ahead of time. If you already have dental issues, you might need to delay treatment or get special care. Skipping this step can lead to painful infections and surgery.

Are these new bone drugs available now?

Most are still in clinical trials. Romosozumab and DKN-01 are being tested in phase III studies like BONE-HEAL (NCT05218913). They’re approved for osteoporosis but not yet for multiple myeloma. Some doctors may prescribe them off-label for patients with severe bone damage who haven’t responded to standard treatment. Check with your oncologist about ongoing trials at major cancer centers - Mayo Clinic, Dana-Farber, and MD Anderson all have active studies.

How do I know if I’m a candidate for a new bone-building drug?

You may be a candidate if you’ve had multiple fractures, your bone scans show worsening lesions despite standard treatment, or your blood tests show high levels of DKK1 or sclerostin. Your doctor may order a bone turnover marker test (like serum CTX or P1NP) to see how fast your bone is breaking down or rebuilding. If your markers show high resorption and low formation, you’re likely a good fit for drugs that stimulate bone growth. Clinical trials often require these specific biomarkers to qualify.

Olivia Portier

December 9, 2025 AT 16:59OMG this post made me cry 😭 I’ve been on denosumab for 2 years and my spine finally stopped crumbling. I can pick up my kid again. Who knew bone could heal?!

Tiffany Sowby

December 11, 2025 AT 07:08Yeah right. Big Pharma’s latest money grab. They’ve been selling ‘bone rebuilding’ for 20 years. Just give me a pill that doesn’t cost a mortgage.

Asset Finance Komrade

December 13, 2025 AT 02:12One must consider the ontological implications of bone regeneration in the context of neoplastic microenvironments. Is healing not merely an illusion of homeostasis? The body, after all, is a transient equilibrium of decay and reassembly - a Hegelian dialectic of cellular strife.

Jennifer Blandford

December 14, 2025 AT 21:06Y’ALL. I just got my DKK1 results - 67.2 pmol/L. My oncologist said I’m a candidate for the BONE-HEAL trial. I’m crying. I’m booking a flight to Mayo. This is real. This is hope. 🙏

Brianna Black

December 15, 2025 AT 04:26As a former clinical trial coordinator at Johns Hopkins, I can confirm the data on romosozumab is robust. The 53% BMD increase is statistically significant (p<0.001). What’s more, patient-reported pain scores improved in 92% of cases. This isn’t hype - it’s science.

Andrea Petrov

December 16, 2025 AT 08:41Ever wonder why these drugs aren’t FDA-approved yet? Coincidence that the same companies that make chemo also own the patents? The FDA is a puppet. They’re waiting for the right moment to monetize. You’re being used as lab rats.

Suzanne Johnston

December 18, 2025 AT 05:48It’s fascinating how we’ve spent decades treating bone damage as a side effect - not the core pathology. Maybe the real breakthrough isn’t the drug, but the shift in mindset. The bone isn’t broken. The system is. We’re finally treating the whole war, not just the bullets.

Graham Abbas

December 19, 2025 AT 07:22My dad’s been on zoledronic acid since 2019. His teeth are toast. He can’t eat a carrot. But he’s alive. I don’t know what’s worse - the cancer or the cure. I just wish someone had warned us about MRONJ before he lost three molars.

Haley P Law

December 20, 2025 AT 02:30So… we’re saying we can actually rebuild bone now?? Like… with magic?? 😱 I need to send this to my cousin in Texas. She’s been begging her oncologist for something new for 4 years. This is the answer!!

Carina M

December 20, 2025 AT 07:36It is imperative to note that the use of anti-sclerostin agents in the context of myeloma remains investigational. To advocate for off-label prescribing without long-term safety data constitutes a breach of medical ethics and patient autonomy.

William Umstattd

December 21, 2025 AT 07:08Correction: The STRUCTURE trial reported a 53% increase in lumbar spine BMD, not ‘spine’ generically. Precision matters. Also, the sample size was 49 - statistically underpowered for clinical endpoints. Don’t oversell.

Elliot Barrett

December 22, 2025 AT 00:03Yeah, yeah. New drugs. Cool. But I’ve been on denosumab since 2020 and still got a compression fracture last month. So tell me again how this is gonna change anything?

Tejas Bubane

December 23, 2025 AT 18:32US doctors are so obsessed with fancy drugs. In India we use bisphosphonates, calcium, vitamin D and walk 10k steps daily. No one needs $2500 shots. You people overmedicalize everything.

Ajit Kumar Singh

December 23, 2025 AT 19:14My wife’s DKK1 was 89.3… we got into the trial… she’s walking again… thank you to the scientists… this is real… I’m not crying… you’re crying…

Maria Elisha

December 23, 2025 AT 21:36So… can I just take a supplement instead? Like, collagen or something? I’m not paying $2k a shot.