What Is Pleural Effusion?

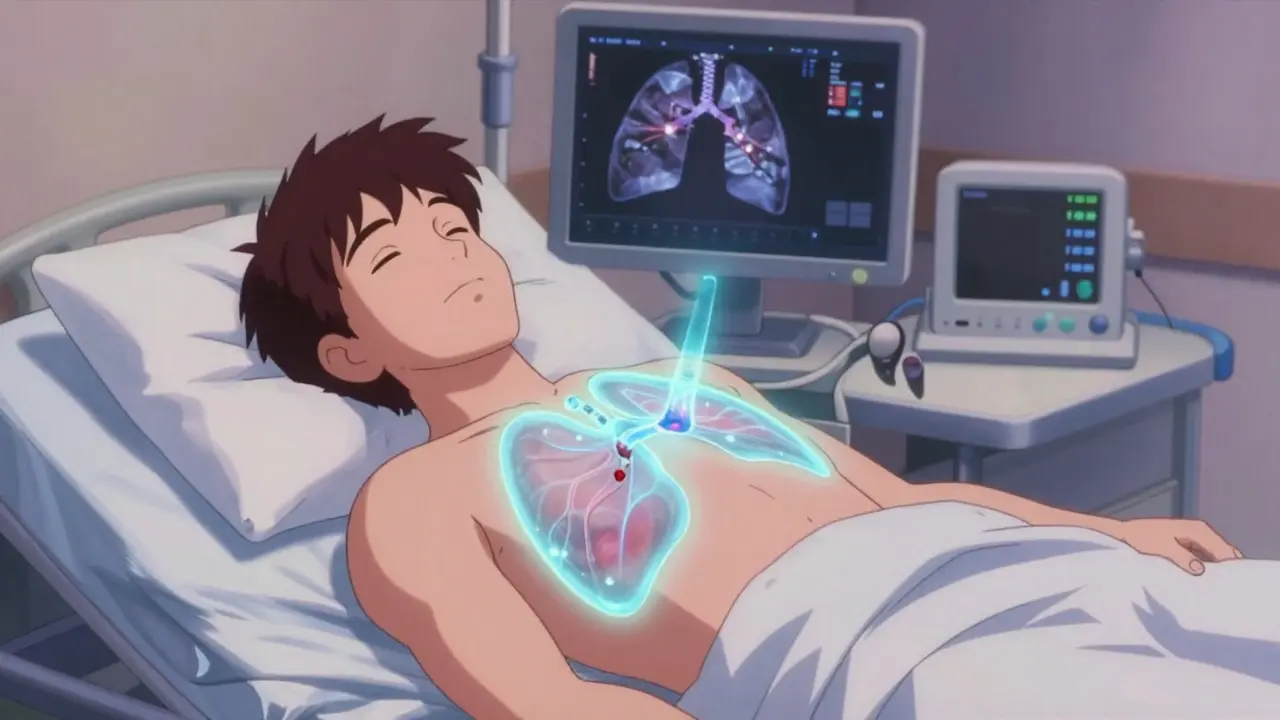

When fluid builds up between the layers of tissue lining your lungs and chest wall, that’s a pleural effusion. It’s not a disease itself-it’s a sign something else is wrong. Think of it like swelling around your lungs. That extra fluid pushes on your lungs, making it hard to breathe, especially when you lie down or move. You might also feel a sharp pain when you inhale, or have a dry cough. It’s common, affecting about 1.5 million people in the U.S. every year.

Not all pleural effusions are the same. They fall into two main types: transudative and exudative. Transudative means fluid is leaking because of pressure changes-like when your heart isn’t pumping well and fluid backs up. That’s the case in about half of all pleural effusions, mostly from congestive heart failure. Exudative means inflammation or infection is making blood vessels leaky. That’s often from pneumonia, cancer, or a blood clot in the lung.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

The cause tells you what to do next. If you ignore the root problem, the fluid will come back-no matter how much you drain.

- Congestive heart failure is the #1 cause of transudative effusions. When the heart can’t pump blood effectively, pressure builds in the veins, pushing fluid into the pleural space. About 90% of transudative cases come from this.

- Pneumonia is the leading cause of exudative effusions. When infection hits the lung, it triggers inflammation that makes fluid leak into the chest cavity. About 40-50% of exudative cases are from pneumonia.

- Cancer, especially lung, breast, or lymphoma, causes 25-30% of exudative effusions. Tumors irritate the pleura or block lymphatic drainage, letting fluid accumulate. Left untreated, malignant effusions cut median survival to just 4 months.

- Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung) causes 5-10% of cases. It triggers inflammation and fluid buildup without infection.

- Cirrhosis and nephrotic syndrome are less common but important. In liver disease, low protein levels let fluid escape. In kidney disease, protein leaks into urine, lowering blood pressure and pulling fluid out.

Here’s the key: 25% of effusions initially labeled "undetermined" turn out to be cancer. That’s why doctors don’t just shrug and say "it’s probably heart failure." They test the fluid.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors start with a chest X-ray or ultrasound. If they see fluid, they need to know what kind it is. That’s where Light’s criteria come in-developed in 1972 and still the gold standard today.

Light’s criteria look at three things in the fluid:

- Pleural fluid protein divided by serum protein > 0.5

- Pleural fluid LDH divided by serum LDH > 0.6

- Pleural fluid LDH > two-thirds of the normal upper limit for blood LDH

If any one of these is true, it’s an exudative effusion. This test is 99.5% accurate at catching exudates. That’s why it’s used everywhere-from small clinics to big hospitals.

But that’s not all. Other tests tell you more:

- Pleural fluid pH below 7.2 means a complicated parapneumonic effusion-you’re at risk for empyema (pus in the chest).

- Glucose below 60 mg/dL suggests infection, rheumatoid arthritis, or tuberculosis.

- LDH over 1,000 IU/L is a red flag for cancer.

- Cytology (looking for cancer cells under a microscope) finds malignant cells in about 60% of cases.

- Amylase levels high? Could be pancreatitis.

- Hematocrit over 1% in the fluid? Could mean a pulmonary embolism or infection.

Ultrasound is now required before any procedure. It shows exactly where the fluid is and helps avoid poking the lung by accident.

What Is Thoracentesis?

Thoracentesis is the procedure to drain the fluid. It’s simple, quick, and usually done in an outpatient setting. But it’s not just about relief-it’s diagnostic.

Doctors use ultrasound to find the safest spot, usually between the 5th and 7th ribs on your side. A thin needle or catheter goes in, and fluid is pulled out. For diagnosis, they take 50-100 mL. For symptom relief, they might take up to 1,500 mL in one go.

Complications happen in 10-30% of cases without ultrasound. With it? That drops to 4-5%. The biggest risk is a collapsed lung (pneumothorax), which happens in 6-30% of unguided procedures. Ultrasound cuts that risk by 78%.

Another rare but serious risk is re-expansion pulmonary edema. That’s when the lung fills with fluid too fast after being collapsed. It’s rare-under 1%-but more likely if you drain more than 1,500 mL at once. That’s why doctors now use pleural manometry: they measure pressure as they drain. If pressure drops below 15 cm H₂O, they stop. That keeps the lung safe.

After the procedure, you’ll get a follow-up X-ray to make sure your lung didn’t collapse. You might feel a little sore or have a cough for a day or two. That’s normal.

How Do You Prevent It From Coming Back?

Draining fluid once doesn’t fix the problem. The fluid comes back if the cause isn’t treated. Prevention depends entirely on why it happened.

If it’s from heart failure: Focus on your heart. Diuretics like furosemide help. ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and monitoring NT-pro-BNP levels (a blood marker for heart strain) can reduce recurrence from 40% to under 15% in three months. No pleurodesis needed-just better heart care.

If it’s from pneumonia: Antibiotics are key. But if the fluid is thick, has low pH (<7.2), low glucose (<40 mg/dL), or shows bacteria on a Gram stain, you need to drain it fully. If you don’t, 30-40% of cases turn into empyema, which needs surgery.

If it’s from cancer: This is where things get serious. Without treatment, 50% of malignant effusions return within 30 days after a single drainage. The two main options are:

- Talc pleurodesis: Doctors inject sterile talc into the chest space. It causes inflammation that glues the lung to the chest wall. Success rate: 70-90%. But it’s painful-60-80% of patients need strong pain meds.

- Indwelling pleural catheter (IPC): A small tube stays in place for weeks. You drain fluid at home as needed. Success rate: 85-90% at 6 months. Hospital stays drop from 7 days to 2 days. Many patients prefer this because they can manage it themselves and avoid hospital visits.

Recent studies show IPCs are now the first-line choice for malignant effusions, especially if the lung can’t fully expand (trapped lung). They’re less invasive, just as effective, and improve quality of life.

After heart surgery: About 15-20% of patients get fluid buildup. Most clear up on their own. But if more than 500 mL drains per day for three days straight, doctors leave a chest tube in longer-often for a week or more. That prevents recurrence in 95% of cases.

What Should You Avoid?

Don’t let anyone drain your fluid just because they see it on a scan. A 2019 JAMA study found that 30% of thoracentesis procedures were done on small, asymptomatic effusions-and provided zero benefit. You don’t need a needle if you’re not short of breath and the cause is clear.

Also, don’t assume it’s heart failure just because you have a history of it. Cancer can hide behind a "benign" label. Always insist on fluid analysis if the effusion is larger than 10 mm on ultrasound.

And never skip follow-up. If your fluid comes back, it’s not just annoying-it’s a warning sign. Your doctor needs to reassess the cause. New treatments for cancer, like targeted therapies and immunotherapy, have improved survival for malignant effusion patients from 10% to 25% over the last decade. But only if you catch it early and treat it right.

What’s New in Treatment?

The biggest shift in the last five years? Moving away from one-size-fits-all. Treatment now depends on your cancer type, your overall health, and whether your lung can re-expand.

Doctors are also using biomarkers more. Pleural fluid pH and glucose aren’t just lab numbers-they guide decisions. A pH below 7.2 means you need drainage now, not later. A glucose below 40 means infection is likely. These aren’t optional tests anymore.

And the future? Personalized care. A 2023 Yale study showed recurrence rates for malignant effusions dropped from 50% to 15% when treatment was matched to the specific cancer type and the patient’s performance status. That’s the future: not just treating fluid, but treating you.

Tim Goodfellow

December 17, 2025 AT 15:18Also, pleural manometry? That’s next-level stuff. Doctors aren’t just draining anymore-they’re measuring pressure like it’s a science experiment. Love it.

Takeysha Turnquest

December 18, 2025 AT 02:02Lynsey Tyson

December 18, 2025 AT 06:25Edington Renwick

December 18, 2025 AT 14:53Sarah McQuillan

December 19, 2025 AT 09:23anthony funes gomez

December 19, 2025 AT 19:19pascal pantel

December 19, 2025 AT 20:50Gloria Parraz

December 21, 2025 AT 02:17Sahil jassy

December 21, 2025 AT 18:39❤️

Kathryn Featherstone

December 22, 2025 AT 00:25Henry Marcus

December 23, 2025 AT 10:57Carolyn Benson

December 23, 2025 AT 16:56Aadil Munshi

December 23, 2025 AT 20:07