Not all generic drugs are created equal. While you might think a generic version of a brand-name drug is just a cheaper copy, that’s not true for complex generic drugs. These aren’t simple pills with the same active ingredient as the original. They’re liposomal injections, inhalers with precise device mechanics, long-acting injectables, or peptide-based therapies. And getting them approved by the FDA? It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

What Makes a Generic Drug "Complex"?

The FDA defines complex generic drugs by five key traits: complex active ingredients, intricate formulations, unusual dosage forms, tricky delivery methods, or drug-device combinations. Think of it like this: a regular generic aspirin is easy to copy. But a liposomal bupivacaine injection? That’s a different story. The drug isn’t just floating in liquid-it’s trapped inside tiny fat bubbles designed to release slowly over days. To prove it works the same as the brand version, you can’t just measure blood levels. You have to show the entire delivery system behaves identically, from how the bubbles form to how they break down in the body.

Other examples include inhalers where the shape of the nozzle or the pressure of the puff changes how much drug reaches the lungs. Even a 0.1-millimeter difference in the device can trigger a regulatory red flag-even if patients wouldn’t notice any difference in how they feel. Peptide drugs, which are chains of amino acids, are another headache. They’re fragile, hard to replicate exactly, and can trigger immune reactions if even one molecule is slightly off. These aren’t just technical problems-they’re scientific puzzles that require advanced labs, specialized equipment, and deep expertise most generic manufacturers don’t have.

Why the Traditional Approval Path Doesn’t Work

For simple generics, the FDA uses the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. It’s fast because it lets companies skip costly clinical trials-they just need to prove their drug is bioequivalent to the brand. But bioequivalence doesn’t mean the same thing for complex drugs. For a pill, you measure how fast the drug enters the bloodstream. For a liposomal injection? That number doesn’t tell you if the drug is being delivered the right way, at the right speed, to the right place.

That’s why the FDA created the Pre-ANDA Meeting Program under GDUFA II in 2017. It’s a way for generic makers to sit down with FDA scientists before they even start testing. They can ask: "What data do you need? What methods work?" By 2023, over 1,200 of these meetings had been held. But even then, companies often walk away confused. Without clear, published guidance, FDA expectations can shift between reviewers. One team might want three different analytical tests. Another might ask for animal studies. No one knows for sure until they submit-and then they get rejected.

The Data Doesn’t Lie: Approval Rates Are Shockingly Low

Since 2015, only about 15 complex generic drugs have been approved by the FDA. In the same time frame, more than 1,000 simple generics got the green light. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a system mismatch. The FDA has tried to fix this with Product-Specific Guidances (PSGs)-detailed documents that spell out exactly what’s needed for each complex product. As of 2023, there are over 1,700 PSGs available. But here’s the catch: only a fraction of complex products have one. And even when they do, manufacturers often spend years trying to meet them.

Take the case of bupivacaine liposome injectable, approved in 2019. It was the first complex generic approved under a new bioequivalence method. It took over a decade of back-and-forth with the FDA. The manufacturer had to develop entirely new testing protocols, run dozens of stability studies, and prove the liposomes behaved the same way in human tissue. It cost an estimated $40 million and took six years. Most small generic companies can’t afford that risk.

Costs and Timelines Are a Major Barrier

Developing a simple generic? That can cost $2 million to $5 million and take 2-3 years. A complex generic? $20 million to $50 million. Five to seven years. That’s not just more money-it’s more time, more risk, more staff, more labs. And if the FDA rejects your application after all that? You’re out millions with nothing to show for it.

Companies have to choose: invest in a complex generic and risk financial ruin, or stick with easy generics that bring low margins but guaranteed approval. That’s why so few companies even try. The market could be worth $75 billion annually as branded complex drugs lose patent protection by 2028. But if no one can get them approved, patients won’t get cheaper options.

Regulatory Hurdles Around the World

The problem isn’t just in the U.S. In China, the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) requires local clinical trials and a legal agent based in-country. The review process can take two years just to start. Brazil’s ANVISA demands that all labs and clinical sites follow strict ICH guidelines, which many generic manufacturers in India or Southeast Asia can’t afford to certify. Even if a company solves the science in the U.S., they can’t sell it elsewhere without jumping through another country’s hoops.

And it’s not just about approval-it’s about access. The Commonwealth Fund found that most new generics approved since 2016 aren’t first-time generics. They’re fourth or fifth versions of drugs already on the market. That means more competition, but not necessarily lower prices for patients. The real need-drugs with no generics at all-often gets ignored.

What’s Changing? And What’s Still Broken

The FDA has made real progress. They’ve hired 128 new reviewers for generic drugs. They’ve cut review times from 31 months in 2012 to under 10 months for original applications as of 2023. They’re investing in AI and machine learning to predict bioequivalence without full clinical trials. Quality-by-design approaches are helping manufacturers build better products from the start, reducing back-and-forth with regulators.

But the system is still built for simplicity. Complex generics require a different kind of science-and a different kind of regulation. Right now, the FDA is trying to fit square pegs into round holes. They’re using the same review team for a pill and a liposomal injection. They’re asking the same questions for a drug you swallow and one you inhale. That’s why progress is slow.

Experts agree: the future lies in smarter tools. Orthogonal testing (using multiple methods to confirm results), dynamic regulatory checklists, and AI-driven data analysis could cut development time by 20-30% by 2027. But that requires investment-not just from manufacturers, but from regulators too. The FDA needs more scientists who understand advanced formulations. They need to publish PSGs faster. And they need to stop treating complex generics like they’re just regular pills with fancy packaging.

Who Gets Left Behind?

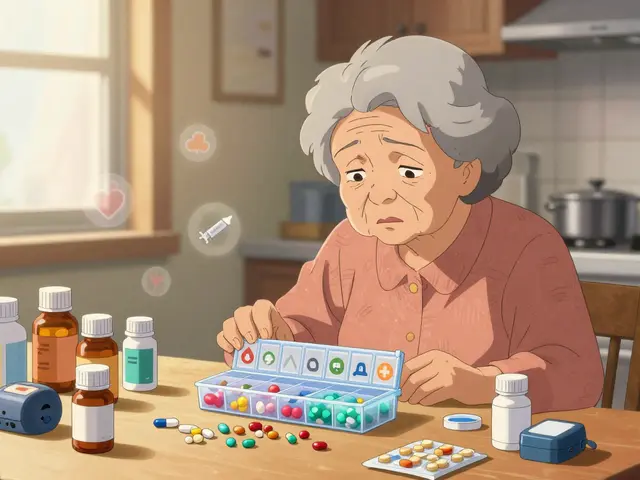

Patients. That’s who. When a complex generic doesn’t get approved, patients pay more. They might have to use a brand-name drug that costs $10,000 a year instead of a $2,000 generic. Or they might have to switch to a less effective treatment because the complex version they need isn’t available. This isn’t just about profit margins-it’s about access to care.

Health Affairs pointed out in 2021 that the FDA doesn’t track which drugs patients can’t access. There’s no system to say: "This is the drug cancer patients need most, and no generic exists." Without that focus, the system keeps approving easy generics while the hardest, most needed ones sit on the shelf.

The solution isn’t just more funding or faster reviews. It’s a mindset shift. Complex generics aren’t just harder to make-they’re harder to regulate. And until the FDA treats them as a separate category with separate rules, they’ll keep failing to deliver what patients need.

Kiranjit Kaur

December 22, 2025 AT 04:40Jim Brown

December 23, 2025 AT 04:16Sam Black

December 23, 2025 AT 11:36Jamison Kissh

December 24, 2025 AT 03:39Nader Bsyouni

December 25, 2025 AT 04:56Julie Chavassieux

December 25, 2025 AT 13:35Tarun Sharma

December 27, 2025 AT 01:59Cara Hritz

December 28, 2025 AT 22:31Kathryn Weymouth

December 29, 2025 AT 20:02Herman Rousseau

December 31, 2025 AT 17:47Vikrant Sura

January 1, 2026 AT 03:00