Water Safety Risk Checker

Select your primary water source to check its risk level for salmonellosis:

Risk Assessment Result

Learn about effective water treatments to prevent salmonellosis:

Boiling

Bring water to a rolling boil for at least one minute to kill 99.9% of pathogens including Salmonella.

Filtration

Use certified point-of-use filters (0.2-micron) to remove bacteria and protozoa from water.

Disinfection

Add unscented household bleach (5–6% sodium hypochlorite) at 2 drops per liter and let sit 30 minutes.

Storage

Store treated water in closed, food-grade containers to prevent re-contamination.

| Source | Typical Treatment | Contamination Risk | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal tap | Chlorination, filtration | Low (but vulnerable during outages) | Use boil water notice guidelines |

| Private well | Often none; depends on homeowner | Moderate-High (surface runoff) | Annual testing + filtration/boiling |

| Surface water (river, lake) | Variable; sometimes untreated | High (animal waste, runoff) | Never drink untreated; always treat |

| Bottled water | Manufacturing filtration & disinfection | Low (if sealed) | Check seal; store away from heat |

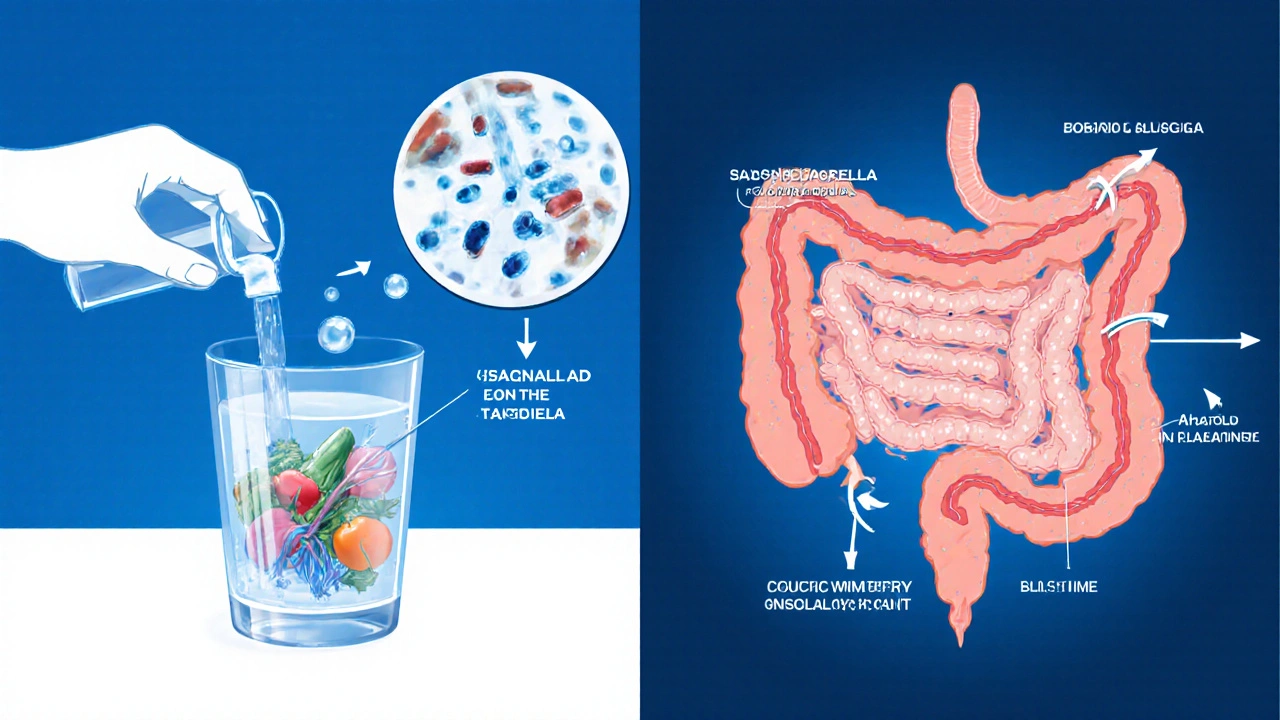

Ever wondered why a glass of water can sometimes make you sick? The link between salmonellosis and unsafe water is more common than you think, especially in areas with lax sanitation. This guide breaks down what the disease is, how tainted water spreads it, and what you can do to stay safe.

What is Salmonellosis is an infection caused by Salmonella bacteria that typically affects the intestines, leading to diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramps?

Salmonellosis is a type of food‑borne and water‑borne illness. The culprit, Salmonella is a genus of rod‑shaped, gram‑negative bacteria that live in the intestines of animals and humans, can invade the human gut when ingested. While most cases stem from undercooked poultry or eggs, contaminated water accounts for a sizable share of outbreaks, especially in developing regions and during natural‑disaster recovery.

How does contaminated water is water that contains harmful microorganisms, chemicals, or particles that can cause disease when consumed or used for hygiene become a carrier for Salmonella?

Water becomes contaminated in several ways. Animal waste, especially from livestock, often runs off into rivers, lakes, and groundwater. If sewage systems leak or are poorly treated, fecal coliform is a group of bacteria used as an indicator of fecal contamination in water levels rise, signaling the possible presence of pathogens like Salmonella. In rural settings, private wells can draw water directly from contaminated aquifers, while municipal supplies may suffer from pipe breaks that allow surface water to mingle with drinking water.

Pathways: From Water to Your Gut

- Ingestion: Drinking untreated water or using it to make ice, coffee, or smoothies.

- Food preparation: Washing fruits, vegetables, or rice with contaminated water, then eating them raw.

- Personal hygiene: Using contaminated water for hand‑washing after handling raw meat can spread bacteria to the mouth.

Each pathway introduces Salmonella into the digestive tract, where it overcomes stomach acid, adheres to the intestinal lining, and multiplies, leading to the classic symptoms.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Typical symptoms appear 6‑72 hours after exposure and last 4‑7 days:

- Watery or bloody diarrhea

- Abdominal cramps

- Fever (often 101‑104°F/38‑40°C)

- Nausea and occasional vomiting

Because symptoms overlap with other gastroenteritis causes, lab testing is essential. A stool culture identifies Salmonella as the pathogen. In severe cases, a blood culture may be ordered to check for systemic spread, especially in infants, the elderly, or immunocompromised patients.

Treatment Options

Most healthy adults recover with supportive care-plenty of fluids, electrolytes, and rest. However, certain groups need medical intervention:

- Antibiotics are medications such as ciprofloxacin or azithromycin used to kill or inhibit bacterial growth are prescribed for infants, pregnant women, or people with weakened immune systems.

- Severe dehydration may require intravenous (IV) fluids, especially in children.

- Probiotics can help restore gut flora after the infection clears.

The CDC is the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a federal agency that monitors and provides guidance on infectious diseases recommends contacting a healthcare provider if symptoms exceed three days, if blood appears in stool, or if fever persists.

Prevention and Safe Water Practices

Preventing salmonellosis starts with breaking the contamination cycle. Here are proven tactics:

- Boiling: Bring water to a rolling boil for at least one minute. This kills 99.9% of pathogenic bacteria, including Salmonella.

- Filtration: Use certified point‑of‑use filters (e.g., 0.2‑micron) that remove bacteria and protozoa.

- Disinfection: Add unscented household bleach (5-6% sodium hypochlorite) at 2drops per liter, let sit 30minutes before use.

- Safe storage: Keep treated water in closed, food‑grade containers to avoid re‑contamination.

- Hygiene: Wash hands with soap and safe water for at least 20 seconds after using the bathroom and before handling food.

- Food safety: Rinse produce with treated water, cook meat to internal temperatures of165°F (74°C), and avoid cross‑contamination.

Public utilities must maintain chlorination is a water treatment process that adds chlorine to kill harmful microbes and conduct regular testing for coliforms. Rural households should test well water quarterly using EPA‑approved kits.

Checklist: Is Your Water Safe?

- Do you know the source of your drinking water (municipal, well, surface)?

- Has the water been tested for fecal coliform in the past six months?

- Do you boil or filter water during boil‑water advisories?

- Is your home’s plumbing free of cracks and leaks?

- Do you practice proper hand‑washing with safe water?

- Are you aware of local outbreak alerts from public health agencies?

Risk Comparison of Common Water Sources

| Source | Typical Treatment | Contamination Risk | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal tap | Chlorination, filtration | Low (but vulnerable during outages) | Use boil water notice guidelines |

| Private well | Often none; depends on homeowner | Moderate‑High (surface runoff) | Annual testing + filtration/boiling |

| Surface water (river, lake) | Variable; sometimes untreated | High (animal waste, runoff) | Never drink untreated; always treat |

| Bottled water | Manufacturing filtration & disinfection | Low (if sealed) | Check seal; store away from heat |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get salmonellosis from bottled water?

Only if the bottle is compromised-e.g., cracked, opened, or stored in unsanitary conditions. Properly sealed bottles are generally safe.

How long should I boil water to kill Salmonella?

A rolling boil for at least one minute is sufficient at altitudes up to 6,500feet. Higher altitudes require two minutes.

Is chlorination enough to make well water safe?

Chlorination can reduce bacterial load, but it doesn’t remove chemicals or sediments. Combining chlorination with filtration provides broader protection.

Should children be given antibiotics for salmonellosis?

Only under a doctor’s direction. In most cases, children recover with fluid therapy. Unnecessary antibiotics can cause side effects and resistance.

What’s the best home test for water contamination?

EPA‑approved kits that detect total coliform and E.coli are reliable and easy to use. They give results within 24‑48hours.

Rebecca M

October 8, 2025 AT 14:14When discussing waterborne salmonellosis, it is essential to recognize that the pathogen thrives in environments where organic matter accumulates, especially in stagnant or poorly treated supplies; consequently, exposure risk escalates dramatically. Accurate identification of water source characteristics, such as municipal chlorination levels, private well vulnerabilities, and surface water contamination pathways, provides a foundation for risk mitigation; this is why detailed assessments are indispensable. Boiling water for a full minute eliminates up to 99.9% of bacterial agents, including Salmonella, thereby offering immediate protection; however, boiling alone does not address chemical pollutants, which may persist. Filtration systems rated at 0.2 microns effectively remove bacterial cells, yet their performance depends on proper maintenance, regular cartridge replacement, and verification of flow rates; neglect in any of these areas compromises efficacy. Disinfection with unscented household bleach, applied at two drops per liter, creates a potent oxidative environment that inactivates pathogens within thirty minutes, but user error in dosage or contact time can diminish results; caution is advised.

Storage practices further influence safety: sealed, food‑grade containers prevent post‑treatment recontamination, a step often overlooked in casual settings. Personal hygiene, especially hand‑washing after restroom use, curtails the transfer of fecal bacteria to food items, a conduit frequently implicated in outbreak scenarios; the CDC emphasizes this as a cornerstone of prevention. Regular testing of private wells for total coliform and E. coli, using EPA‑approved kits, yields actionable data, enabling timely interventions before widespread illness occurs. Community education campaigns, reinforcing these protocols, have demonstrably reduced infection rates in regions previously afflicted by endemic contamination. Ultimately, a layered approach-combining source protection, treatment, storage, and behavior change-creates a resilient barrier against salmonellosis, safeguarding public health across diverse settings.

Bianca Fernández Rodríguez

October 18, 2025 AT 09:26Honestly, i think the whole boil‑water advisory thing is overhyped.

Patrick Culliton

October 28, 2025 AT 03:38The article overstates the danger of municipal tap water; most cities already meet stringent safety standards.

Andrea Smith

November 6, 2025 AT 22:50While I respect your perspective, it is prudent to acknowledge that even well‑regulated systems can encounter unexpected failures, thereby justifying precautionary measures.

Gary O'Connor

November 16, 2025 AT 18:02yeah, i’ve seen folks just trusting their well water without ever testing it, lol.

Justin Stanus

November 26, 2025 AT 13:14Reading about those outbreaks makes me feel a deep, lingering unease, as if the invisible microbes are silently plotting against us.

Claire Mahony

December 6, 2025 AT 08:26It is concerning that many overlook basic sanitation practices, resulting in preventable cases of infection.

Andrea Jacobsen

December 16, 2025 AT 03:38Absolutely, reinforcing hand‑washing protocols and regular testing can dramatically reduce risk.

Andrew Irwin

December 25, 2025 AT 22:50I think we can all agree that a balanced approach-combining filtration, boiling when necessary, and community education-offers the best protection.

Jen R

January 4, 2026 AT 18:02Sure, but if you already have a good filter, boiling every time feels like overkill.

Joseph Kloss

January 14, 2026 AT 13:14One might contemplate the paradox of seeking purity in a world where every drop carries the memory of its journey.

Anna Cappelletti

January 24, 2026 AT 08:26Your reflection beautifully reminds us that proactive steps, however small, empower us to safeguard our health.

Dylan Mitchell

February 3, 2026 AT 03:38The saga of contaminated water reads like a thriller, each sip a potential plot twist that could shatter lives.

Elle Trent

February 12, 2026 AT 22:50From a risk‑assessment standpoint, the vulnerability matrix indicates a high probability density for surface water sources.