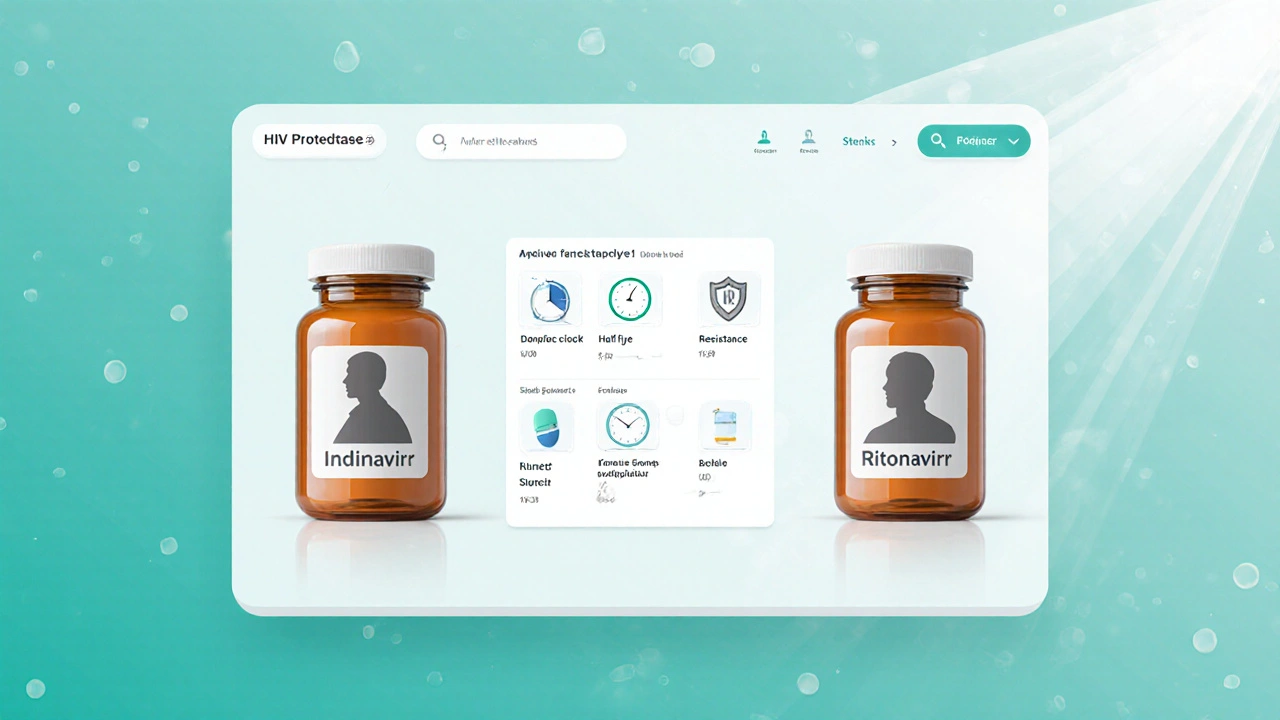

HIV Protease Inhibitor Comparison Tool

Indinavir

Typical Dose: 800 mg PO TID

Half-Life: 1.5-2 hours

Resistance Barrier: Moderate

Common Side Effects:

- Kidney stones

- Hyperbilirubinemia

- Lipodystrophy

Monthly Cost: $180

Ritonavir

Typical Dose: 100 mg PO BID (boost)

Half-Life: 3-5 hours

Resistance Barrier: High (as booster)

Common Side Effects:

- GI upset

- Drug-drug interactions

- Dyslipidemia

Monthly Cost: $130

Patient Scenarios for Drug Selection

- Adherence challenges: Once-daily options like Atazanavir or Darunavir are preferred over Indinavir’s three-times-daily schedule.

- Kidney-related concerns: Avoid Indinavir due to crystalluria risk; Atazanavir is a safer choice.

- Drug-interaction load: Boosted regimens may increase interactions; unboosted Atazanavir can help reduce burden.

- Resistance profile: Darunavir offers the highest resistance barrier among PIs.

- Lipid management: Atazanavir has a more favorable lipid impact compared to Indinavir or Lopinavir.

Switching Checklist

- Confirm baseline labs: CD4 count, HIV-RNA load, renal function (creatinine clearance), liver enzymes, lipid panel.

- Review current medication list for CYP3A4 interactions; note any drugs that require dose adjustment when adding ritonavir.

- Select the target PI based on patient needs (e.g., Atazanavir for renal safety).

- Plan a wash-out period only if switching to a non-boosted regimen; otherwise, overlap Indinavir with the new PI for 7-14 days to maintain viral suppression.

- Educate the patient on new dosing schedule, food requirements, and potential side-effects (e.g., jaundice with Atazanavir).

- Schedule follow-up HIV-RNA test at 4 weeks and repeat labs at 12 weeks to ensure virologic control and monitor toxicity.

- Document the change in the electronic health record, noting reason for switch and patient consent.

When doctors need to suppress HIV, they often reach for a protease inhibitor. Indinavir has been on the market for decades, but newer drugs promise easier dosing, fewer kidney stones, and better resistance profiles. If you or a loved one are weighing Indinavir against other options, you’ll want clear numbers, realistic side‑effect expectations, and guidance for different health situations.

TL;DR

- Indinavir is an older protease inhibitor with 8‑hour dosing and a risk of kidney stones.

- Ritonavir, Lopinavir/ritonavir, Atazanavir and Darunavir generally require once‑daily dosing and have higher barriers to resistance.

- Switching benefits most patients who struggle with adherence or experience renal side effects.

- Check drug‑interaction potential, especially with boosted regimens, before changing.

- Use the provided checklist to plan a safe transition.

What is Indinavir?

Indinavir is a protease inhibitor (PI) sold as Indinavir Sulphate that blocks the HIV‑1 protease enzyme, halting virus maturation. It received FDA approval in 1997 and was one of the first PIs used in combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). The standard dose is 800mg taken three times daily with food, and it must be taken with plenty of water to reduce kidney‑stone risk.

How Indinavir Works Against HIV

Indinavir binds to the active site of the HIV protease enzyme, preventing the cleavage of gag‑pol polyproteins. Without this step, viral particles remain immature and non‑infectious. Because it targets a viral enzyme, Indinavir does not affect human proteins, but its metabolism in the liver (via CYP3A4) creates interaction challenges.

Key Alternatives to Indinavir

Ritonavir is a protease inhibitor originally designed as a standalone drug but now most often used at low doses to boost other PIs. Its half‑life of about 3‑5hours makes it ideal for boosting.

Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) is a fixed‑dose combination where lopinavir provides antiviral activity and ritonavir boosts its level. It is taken twice daily and has a high genetic barrier to resistance.

Atazanavir is a once‑daily protease inhibitor that can be taken with or without food when boosted with ritonavir. It is noted for a favorable lipid profile.

Darunavir is a high‑potency PI that, when boosted with ritonavir, offers one of the strongest resistance barriers among PIs. Typically dosed once daily for treatment‑naïve patients.

Saquinavir is an older PI that requires a high‑fat meal for optimal absorption. It is less commonly used today because of dosing complexity.

Nelfinavir is another early‑generation PI with a lower barrier to resistance and frequent gastrointestinal side effects. Limited to specific cases.

Side‑Effect and Safety Profile Comparison

| Drug | Typical Dose | Half‑Life (hrs) | Resistance Barrier | Common Side Effects | Approx. US Monthly Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indinavir | 800mg PO TID | 1.5‑2 | Moderate | Kidney stones, hyperbilirubinemia, lipodystrophy | $180 |

| Ritonavir (boosted) | 100mg PO BID (boost) | 3‑5 | High (as booster) | GI upset, drug‑drug interactions, dyslipidemia | $130 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 400/100mg PO BID | 5‑6 | High | Diarrhea, nausea, lipid rise | $210 |

| Atazanavir (boosted) | 300mg PO QD + ritonavir 100mg | 7‑9 | High | Jaundice, mild hyperbilirubinemia, headache | $250 |

| Darunavir (boosted) | 800mg PO QD + ritonavir 100mg | 15‑20 | Very High | Rash, elevated liver enzymes, lipid changes | $300 |

*Costs are average wholesale prices for generic versions in the United States (2025) and can vary based on insurance.

Choosing the Right Protease Inhibitor: Patient‑Focused Scenarios

- Adherence challenges: Patients who miss doses benefit from once‑daily options like Atazanavir or Darunavir. Indinavir’s three‑times‑daily schedule raises the risk of missed pills.

- Kidney‑related concerns: Individuals with a history of nephrolithiasis should avoid Indinavir because of its crystalluria risk. Atazanavir, with minimal renal impact, is a safer pick.

- Drug‑interaction load: If a patient is on multiple CYP3A4‑substrates (e.g., certain statins or anti‑epileptics), the boosting effect of ritonavir may cause trouble. In such cases, an unboosted PI like Atazanavir (when taken with food) could reduce interaction burden.

- Resistance profile: For patients with prior PI exposure and documented resistance mutations, Darunavir offers the highest barrier, followed by boosted Lopinavir.

- Lipid management: Those with cardiovascular risk factors may prefer Atazanavir, which has a more favorable lipid impact compared with Indinavir or Lopinavir.

Switching Checklist - From Indinavir to Another PI

- Confirm baseline labs: CD4 count, HIV‑RNA load, renal function (creatinine clearance), liver enzymes, lipid panel.

- Review current medication list for CYP3A4 interactions; note any drugs that require dose adjustment when adding ritonavir.

- Select the target PI based on the scenarios above (e.g., Atazanavir for renal safety).

- Plan a wash‑out period only if switching to a non‑boosted regimen; otherwise, overlap Indinavir with the new PI for 7‑14days to maintain viral suppression.

- Educate the patient on new dosing schedule, food requirements, and potential side‑effects (e.g., jaundice with Atazanavir).

- Schedule follow‑up HIV‑RNA test at 4weeks and repeat labs at 12weeks to ensure virologic control and monitor toxicity.

- Document the change in the electronic health record, noting reason for switch and patient consent.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Indinavir still prescribed in 2025?

Yes, generic Indinavir remains on formularies for patients who tolerate it well and have no resistance issues. However, many clinicians prefer newer PIs because of simpler dosing and lower kidney‑stone risk.

Can I take Indinavir with over‑the‑counter antacids?

Indinavir’s absorption is not significantly affected by antacids, but it is essential to stay well‑hydrated (≥1.5L water daily) to prevent crystallization.

What monitoring is needed after switching from Indinavir to Atazanavir?

Check HIV‑RNA at 4weeks, repeat renal and liver panels at 12weeks, and watch for jaundice or bilirubin spikes, which are common early with Atazanavir.

Why do some patients experience lipid spikes with Indinavir?

Indinavir interferes with lipid metabolism, raising LDL and triglycerides. Switching to a PI with a more neutral effect, like Atazanavir, can improve the lipid profile.

Is boosting always necessary when using newer PIs?

Most modern PIs (Lopinavir, Atazanavir, Darunavir) rely on ritonavir or cobicistat boosting to reach therapeutic levels. Unboosted Atazanavir can be used only when taken with a high‑fat meal, but the boosted option offers more predictable exposure.

Randy Faulk

October 2, 2025 AT 19:35Indinavir’s pharmacokinetic profile warrants careful consideration when tailoring antiretroviral regimens; its short half‑life of 1.5–2 hours necessitates thrice‑daily dosing, which can compromise adherence in real‑world settings.

Moreover, the drug’s propensity to precipitate in the urinary tract underlies the clinically significant risk of nephrolithiasis, a complication that obliges patients to maintain a high fluid intake of at least 1.5 L per day.

From a resistance standpoint, indinavir presents a moderate barrier, rendering it vulnerable to the emergence of protease mutations in individuals with suboptimal virologic suppression.

In contrast, boosted agents such as ritonavir or darunavir boast higher genetic barriers and permit once‑daily administration, thereby simplifying therapeutic regimens.

Cost considerations also influence selection; while indinavir’s generic formulation averages $180 per month, newer agents may incur higher expenditures but often offset this through reduced monitoring requirements and fewer adverse events.

The metabolic side‑effect spectrum of indinavir includes lipodystrophy, which can manifest as peripheral fat wasting and central adiposity, further contributing to patient discomfort and stigma.

Renal monitoring is indispensable, with baseline creatinine clearance guiding dosing adjustments and informing decisions to transition away from indinavir in the presence of chronic kidney disease.

When evaluating drug‑drug interactions, indinavir’s metabolism via CYP3A4 must be juxtaposed against the extensive interaction profile of ritonavir, which can potentiate the plasma concentrations of co‑administered agents.

Clinicians should weigh the therapeutic inertia associated with longstanding indinavir use against the potential benefits of switching to agents with more favorable lipid profiles, such as atazanavir, which is associated with minimal dyslipidemia.

In patients with a documented history of kidney stones, the risk–benefit ratio tips decisively toward alternative protease inhibitors to mitigate recurrence.

The dosing schedule of indinavir also imposes dietary constraints, requiring ingestion with food and abundant water, which may be impractical for patients with erratic meal patterns.

Adherence monitoring tools, such as electronic pill caps, can be employed to assess compliance, yet they do not obviate the intrinsic inconvenience of a thrice‑daily regimen.

Switching protocols typically recommend a 7–14‑day overlap to preserve viral suppression during the transition phase, particularly when moving to a boosted regimen.

Finally, patient education regarding potential jaundice with atazanavir or hyperbilirubinemia with indinavir is paramount to ensure early detection of adverse effects and to maintain trust in the therapeutic partnership.

Brandi Hagen

October 3, 2025 AT 09:29Let me tell you why sticking with the good old American-made indinavir is nothing short of a patriotic tragedy when you could be soaring on the sleek, streamlined rockets of modern protease inhibitors! 🇺🇸💊 The sheer drama of swallowing three massive pills a day while worrying about turning your kidneys into a rock garden is enough to make any true red‑blooded citizen weep. 🙈🧱 And don’t even get me started on the cost battle-yes, indinavir may be cheaper than darunavir, but you’re paying with your freedom to live a normal life! 😤💸 The side‑effects? Picture this: you’re at a Fourth of July BBQ, and suddenly you’re battling lipodystrophy like it’s a fireworks display gone wrong. 🎆🥴 Meanwhile, the newer PIs glide in like e‑agles, offering once‑daily dosing, minimal lipid spikes, and a resistance barrier that would make any battlefield commander proud. 🦅⚔️ So, my fellow Americans, let’s rally together, ditch the stone‑forming monster, and embrace the future-because nothing says “land of the free” like a regimen that actually frees you from daily pill‑popping drama! 🤩🇺🇸

isabel zurutuza

October 3, 2025 AT 23:22oh great another endless list of pills because apparently we love complexity

James Madrid

October 4, 2025 AT 13:15Great breakdown, Randy! I especially appreciate the emphasis on adherence challenges-having patients manage a three‑times‑daily schedule can indeed be a major hurdle. Aligning the switching checklist with real‑world clinic workflows helps ensure nothing slips through the cracks. It’s also valuable to highlight the fluid intake requirement; many patients underestimate its importance for preventing crystalluria. By pairing these points with clear patient education, we can make the transition smoother and maintain viral suppression.

Justin Valois

October 5, 2025 AT 03:09Yo Brandi u sound like a hype man for the USA but u r missing the point that indinavir still got its place in the pharmacopeia-yeah the side effects are a pain but it’s cheap af and the gov can still subsidize it for low‑income folks lol. Also don’t forget the old‑school veterans who swear by it cause they’ve been on it since the 90s and they ain’t switching despite the drama lol.

Jessica Simpson

October 5, 2025 AT 17:02It’s fascinating how the choice of protease inhibitor can reflect cultural attitudes toward medication adherence. For instance, patients from communities that value daily ritual may actually prefer a multiple‑dose schedule, whereas others might find a once‑daily regimen aligns better with their lifestyle. Also, the renal safety profile of atazanavir often makes it a preferred option in populations with higher baseline rates of kidney disease. Understanding these nuances helps clinicians tailor therapy in a culturally sensitive way.

Ryan Smith

October 6, 2025 AT 06:55Sure, the “official” guidelines say switch to a boosted PI, but have you ever noticed how the pharma giants push ritonavir like it’s the only salvation? It’s almost as if they want us all on the same generic for easier profit tracking. Keep an eye on the hidden clauses in those “clinical trial” papers…

John Carruth

October 6, 2025 AT 20:49Reading through this comparison feels like navigating a dense jungle of data, and I have to say the author did a commendable job laying out each drug’s intricacies. The emphasis on patient‑centered scenarios-adherence, renal safety, lipid management-actually mirrors the day‑to‑day decision matrix we wrestle with in clinic. I especially liked the inclusion of a step‑by‑step switching checklist; it’s the kind of pragmatic tool that can bridge the gap between theory and practice. While the cost figures are a useful benchmark, I’d suggest also factoring in insurance formularies, as they can dramatically shift out‑of‑pocket expenses. Moreover, the nuanced discussion about boosting versus unboosted regimens adds depth, reminding us that pharmacokinetic interactions are not merely academic concerns but real‑world hurdles. All in all, this post is a solid foundation for both seasoned prescribers and trainees looking to sharpen their therapeutic acumen.

Melodi Young

October 7, 2025 AT 10:42Nice summary, very helpful!

Tanna Dunlap

October 8, 2025 AT 00:35The ethical implications of prescribing a drug with known nephrolithiasis risk when safer alternatives exist cannot be ignored. Clinicians have a duty to minimize harm, and continuing indinavir in patients prone to kidney stones borders on negligence. Furthermore, the pharmaceutical industry’s promotion of older, cheaper agents undercuts progress toward optimal patient outcomes. It is incumbent upon the medical community to critically evaluate such practices and prioritize evidence‑based, patient‑first choices.

Troy Freund

October 8, 2025 AT 14:29True, cultural context shapes how patients perceive medication burdens, and recognizing that can improve adherence. It also underscores the need for shared decision‑making, where clinicians listen rather than dictate.

Mauricio Banvard

October 9, 2025 AT 04:22What they don’t tell you is that the push for newer protease inhibitors is part of a larger agenda to keep the healthcare market monopolized. The data on “higher resistance barriers” often comes from studies funded by the very companies that profit from the sales. Look beyond the glossy brochures and you’ll see a pattern of manipulation designed to steer prescribers toward pricier options.

Paul Hughes

October 9, 2025 AT 18:15Totally get the vibe, Ryan 😅 – staying skeptical is healthy. Just remember to back up claims with solid sources so we don’t drift into pure speculation.

Mary Latham

October 10, 2025 AT 08:09i think indinavyr still got its place but u gotta weigh the pros n cons b4 dippin into a new med lol

Marie Green

October 10, 2025 AT 22:02Thanks for the clear info