When an older adult suddenly becomes confused, withdrawn, or agitated, families often assume it’s just aging, dementia getting worse, or a bad night’s sleep. But what if it’s something more urgent - and completely reversible? Medication-induced delirium is one of the most common, dangerous, and preventable conditions affecting older adults in hospitals and nursing homes. It’s not normal. It’s not inevitable. And it’s often caused by drugs that are still routinely prescribed.

What Exactly Is Medication-Induced Delirium?

Delirium isn’t just being forgetful. It’s a sudden, dramatic shift in thinking, attention, and awareness that comes on over hours or days. People with delirium may not recognize family members, mix up day and night, talk incoherently, or sit completely still for hours. The key is the sudden change - not a slow decline. And when it’s caused by medications, it’s called medication-induced delirium.It’s not rare. About 1 in 5 hospitalized seniors over 65 develop it. In the ICU, that number jumps to 8 out of 10. And here’s the scary part: patients with delirium are twice as likely to die within a year compared to similar patients without it. Their hospital stays are longer - on average, eight extra days - and their recovery, both physically and mentally, is much worse six to twelve months later.

The biggest trigger? Medications. More than any infection, electrolyte imbalance, or surgery. And unlike those other causes, medication-induced delirium is often preventable - if you know what to look for.

Which Medications Are Most Likely to Cause It?

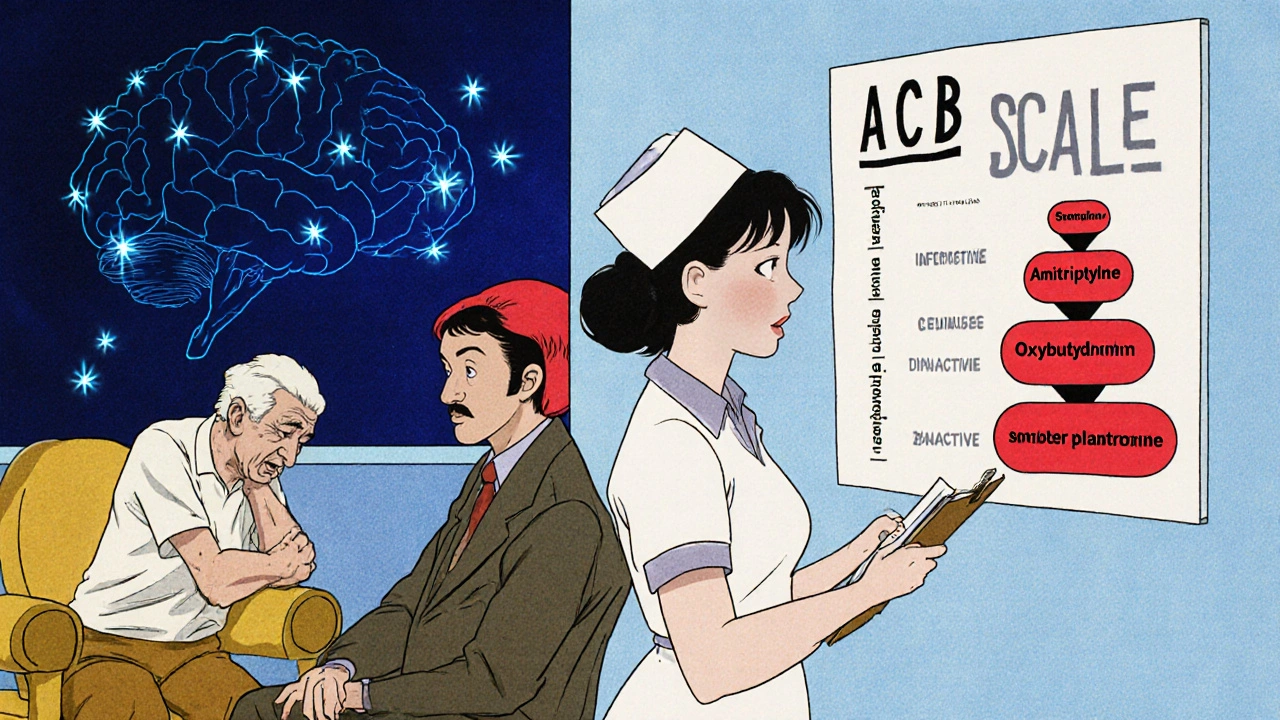

Not all drugs are equal. Some are far more dangerous for older adults because they mess with brain chemicals, especially acetylcholine - the neurotransmitter critical for memory, focus, and alertness.Anticholinergic drugs are the #1 culprit. These include:

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) - still widely sold as a sleep aid or allergy pill

- Oxybutynin (Ditropan) - for overactive bladder

- Amitriptyline - an old-school antidepressant

- Hyoscyamine - used for stomach cramps

These drugs block acetylcholine. In a young person, the brain compensates. In an older adult, especially someone with early dementia, the brain can’t. The result? Confusion, hallucinations, or staring blankly for hours. A 2001 study found that for every increase in anticholinergic burden, delirium severity rose by 80%. Taking three or more of these drugs? That’s a 4.7-times higher risk.

Benzodiazepines - like lorazepam (Ativan) or diazepam (Valium) - are another major problem. They’re often given for anxiety, insomnia, or even to calm agitation. But they slow down brain activity too much. Studies show they increase delirium risk by 3 times. And if someone’s already in the ICU? Their delirium lasts over two extra days.

Opioids - especially morphine and meperidine - can also trigger delirium. Meperidine is particularly risky because one of its breakdown products, normeperidine, overstimulates the brain. Hydromorphone is a safer alternative - it causes 27% less delirium at the same pain-relieving dose.

Even antibiotics like ciprofloxacin and antipsychotics like quetiapine, once thought to be safe, are now on the American Geriatrics Society’s list of high-risk drugs for seniors. Why? They affect brain receptors in ways we didn’t fully understand until recently.

There Are Three Types - And One Is Almost Always Missed

Delirium doesn’t always look like someone screaming or thrashing. In fact, the most common form in older adults is the quiet kind.- Hyperactive delirium: Restless, agitated, hallucinating, yelling. Hard to ignore.

- Hypoactive delirium: Quiet, withdrawn, sleepy, unresponsive. Often mistaken for depression or dementia.

- Mixed delirium: Switches between the two.

Here’s the problem: 72% of medication-induced delirium cases in older adults are hypoactive. And 70% of those go undiagnosed. Nurses and even doctors assume the patient is just tired, sad, or “not themselves because of age.” But it’s not normal. It’s a medical emergency.

Family members often notice it first. A 2020 study found that 89% of caregivers reported a “complete transformation” in their loved one’s personality within 48 hours of starting a new medication. That’s not aging. That’s a red flag.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not every older adult is equally vulnerable. Certain factors make delirium much more likely:- Age over 85 - risk is 2.3 times higher than for those aged 65-74

- Pre-existing dementia - delirium lasts almost twice as long (8.2 days vs. 4.7 days)

- Taking 3+ high-risk medications - 4.7x higher risk

- Recent surgery or hospitalization

- Dehydration or poor nutrition

And here’s something many don’t realize: stopping a drug suddenly can cause delirium, too. If someone’s been on a benzodiazepine for weeks and it’s cut off cold turkey, withdrawal can trigger delirium tremens - a life-threatening condition. Tapering matters.

How to Prevent It - Practical Steps

The good news? You can stop this before it starts. Prevention isn’t complicated - it’s just not done often enough.1. Review every medication - regularly.

Ask the doctor or pharmacist: “Is this still needed? Could it cause confusion?” Use the Beers Criteria - a list of 56+ medications that seniors should avoid. If your loved one is on diphenhydramine, oxybutynin, or amitriptyline, ask if there’s a safer alternative.

2. Use the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) Scale.

This isn’t just a tool for doctors. You can find it online. Each drug gets a score: 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. Add them up. If the total is 3 or higher, delirium risk jumps 67%. That’s your warning sign.

3. Avoid benzodiazepines unless absolutely necessary.

They’re only safe for alcohol withdrawal, seizures, or end-of-life sedation. For anxiety or sleep, try non-drug options: light exposure during the day, no screens before bed, calming music, or melatonin (under supervision).

4. Manage pain without opioids.

Use acetaminophen first. Combine it with heat, ice, physical therapy, or massage. Studies show this cuts opioid use by 37% - and lowers delirium risk.

5. Keep them moving, hydrated, and oriented.

Even small things help: get them up and walking if possible. Keep a clock and calendar visible. Talk to them often. Don’t let them sleep all day. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) reduced delirium by 40% just by doing these simple things.

6. Screen for it.

Ask the hospital staff: “Are you using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)?” It’s a 2-minute test anyone can learn. Hospitals that use it have 32% fewer cases. If they say no - push for it.

What to Do If You Suspect Delirium

If you see sudden confusion, withdrawal, or strange behavior:- Stop all non-essential medications immediately - especially anticholinergics and benzodiazepines

- Call the doctor or nurse - don’t wait

- Bring a full list of all medications, including OTC and supplements

- Ask: “Could this be medication-induced delirium?”

Don’t assume it’s dementia. Don’t assume it’s just “getting old.” Delirium can resolve completely if caught early - sometimes within hours of stopping the offending drug.

Why This Matters Beyond the Hospital

Medication-induced delirium isn’t just a hospital problem. It happens in nursing homes, assisted living, and even at home. And the cost? Over $164 billion a year in the U.S. alone. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now calls hospital-acquired delirium a “never event” - meaning they won’t pay for the extra care it causes.But the real cost is human. A once-independent grandparent becomes dependent. A sharp mind fades. A family’s peace of mind shatters. And too often, it’s because a pill was given without thinking.

With the U.S. population over 65 set to grow from 56 million to 80 million by 2040, this problem is only getting bigger. The FDA now requires stronger warnings on anticholinergic labels. The National Institute on Aging is funding real-time EHR tools to flag risky drug combos. AI is being tested to predict delirium risk before it happens.

But none of that matters if families and caregivers don’t know what to look for - or how to speak up.

Final Thought: You Have Power

You don’t need to be a doctor to protect someone you love. You just need to know the signs. You need to question prescriptions. You need to say: “This change happened right after we started this new pill. What’s going on?”Medication-induced delirium is not a normal part of aging. It’s a warning sign - a signal that something’s wrong. And when you act on it, you’re not just preventing confusion. You’re preserving dignity, independence, and life.

Peter Aultman

November 14, 2025 AT 19:49Man I wish my grandma’s nurse had read this before they gave her Benadryl for sleep. She went from cracking jokes to staring at the wall for three days. Turned out it was the meds. Took weeks for her to bounce back. This needs to be posted in every ER waiting room.

Scarlett Walker

November 15, 2025 AT 16:06This is so important. My aunt was labeled ‘just getting dementia’ until we pulled her off oxybutynin. She remembered my name again after 48 hours. No joke. I’m printing this out and handing it to every doctor I meet.

Jane Johnson

November 15, 2025 AT 22:43While I appreciate the concern for elderly patients, one must consider the broader pharmacological context. The blanket condemnation of anticholinergics ignores individual variability in metabolism and the therapeutic necessity of these agents in certain clinical scenarios. To suggest their universal avoidance is not only reductive but potentially dangerous in the absence of comprehensive patient evaluation.

Anjan Patel

November 16, 2025 AT 19:09THEY KEEP DOING THIS. AGAIN AND AGAIN. OLD PEOPLE AREN’T JUST ‘GETTING WEIRD’ - THEY’RE BEING DRUGGED INTO SILENCE BY DOCTORS WHO DON’T CARE. I’VE SEEN IT. MY GRANDPA WAS A WITTY MAN. THEN THEY GAVE HIM AMITRIPTYLINE. HE STOPPED TALKING. STOPPED EATING. STOPPED LIVING. AND NO ONE LISTENED UNTIL IT WAS TOO LATE. THIS IS MURDER BY PRESCRIPTION.

Hrudananda Rath

November 18, 2025 AT 19:09It is an incontrovertible fact that the contemporary medical establishment has become profoundly derelict in its duty of care toward geriatric populations. The casual prescription of anticholinergic agents - substances known since the 1970s to induce cognitive disintegration in the elderly - reflects not merely negligence, but a systemic epistemic failure. One wonders whether profit margins have superseded Hippocratic ethics entirely.

Brian Bell

November 20, 2025 AT 03:40So true 😔 I just got back from visiting my uncle in rehab - they put him on Ativan for ‘anxiety’ after surgery. He didn’t recognize his own daughter for a week. They finally took it off and he came back to us. Please, if you’re reading this - ask about meds before you sign anything. 💪

Eleanora Keene

November 21, 2025 AT 02:12Thank you for writing this. I’ve been pushing my mom’s doctor to review her meds for months and he kept saying ‘she’s fine.’ This gave me the courage to push harder. I printed the Beers Criteria list and handed it to him. He actually changed two prescriptions. Small win - but it matters. You’re not alone in this fight.

Joe Goodrow

November 21, 2025 AT 16:09Why are we letting foreign drug companies dictate how our seniors are treated? These meds are banned in Europe for a reason. We need real oversight - not just ‘guidelines’ that get ignored. This is why America’s healthcare system is broken. Stop outsourcing common sense.

Kevin Wagner

November 22, 2025 AT 21:25Let me tell you something - if you’re giving an 80-year-old diphenhydramine like it’s candy, you’re not helping. You’re playing Russian roulette with their brain. I’ve seen people wake up from delirium like they’re coming out of a coma. And the worst part? They remember every second of it. That’s not aging. That’s malpractice dressed up as medicine. Fight back. Ask the questions. Demand alternatives. Your loved one’s mind is worth more than a quick fix.